By Markham Cheever (1918 – 2005)

Markham Cheever joined the DEWLine project on a special assignment as Building Engineer in 1953 and was ultimately promoted to Superintendent of Construction for the entire project, which extended some 3000 miles from the west coast of Alaska to the east coast of Baffin Island.

Markham’s notes (below) are extremely important because they are the only known record of the heretofore poorly documented part of DEWLine history, the years before the Line became operational This document provides a unique insight into what was involved in bringing this massive project to a successful conclusion.

Markham Cheever, in an Anson with his ever present red cap, enroute to an unnamed site. Aug 26, 1956.

Our thanks to both Paul and Will Cheever for their permission to publish their Father’s notes. Here then, are Markham Cheever’s unedited notes from 1995.

MARKHAM S. CHEEVER (1918-2005)

Participation in DEW Line Project

January 1953-November 1953

October 1954-September 1957

INTRODUCTION

June 1995

The DEW Line – acronym for Distant Early Warning Line – is a chain of radar stations installed north of the Arctic Circle extending 3,000 miles from the Bering Strait in the west to the eastern shore of Baffin Island. Conceived in 1952, its purpose was to provide United States and Canada the earliest possible warning of subsonic aircraft and missiles approaching North America from the polar region.

In the early stages of the Cold War with the Soviet Empire, Russian military planes were known to be flying reconnaissance missions over Alaska and deep into central Canada. Detection of these was, at best, random but the fact of these intrusions was well known and was occasionally the subject of articles in the press. (I recall one in the New York Times circa 1950.)

At the request of USAF, a group of scientists convened at MIT in 1952 to evaluate the potential threat to national security and make recommendations for countermeasures. From this came the concept of the DEW Line. It required pushing the envelope of several technologies well beyond the (then) current state of the art.

- Acquisition radar twice more powerful than current apparatus.

- A communications system which would perform with 99 percent reliability. To that date, electromagnetic disturbances in the Arctic could blank out radio reception for extended periods.

- Building and outside plant designs that could –

- be habitable and survive for 15 years in the Arctic

- be transported to and erected in the Arctic

- Selection of sites to meet criteria for operation of radar and radio, which at the same time could be accessed for construction and were logistically supportable.

Contributing to the enormity of the task were the innumerable unknowns of geography (sketchy or nonexistent topographical data), climatology (temperature ranges, wind directions and velocities, precipitation), soil conditions (permafrost depth, availability of gravel, subsurface soil conditions), and oceanography (ice conditions, water depth, and currents which would affect the seaborne delivery of cargo). A fair amount was known of the north slope of Alaska. The U.S. Navy had established an arctic research lab at Pt. Barrow and had conducted extensive exploration for oil and gas in that area since 1946. In the Canadian arctic, information was spotty. There was a WWII paved airstrip and hangar at Frobisher Bay on Baffin Island (below the Arctic Circle).

The lonely (and unused) LORAN tower at Cambridge Bay.

At Cambridge Bay on Victoria Island was a Hudson Bay Co. post, an RCAF arctic survival camp, and a LORAN tower deactivated except for an aircraft radio beacon. Otherwise, there was but a sparse scattering of weather stations, Hudson Bay posts, and native Eskimo villages. Large areas, such as the interior of Baffin Island, were unmapped.

The prime contractor for the project was the Western Electric Co. who published the two booklets titled “The DEW Line Story.” They are similar yet different in the information they convey. Together they give a credible account of an incredibly large and complex technical and logistic venture undertaken jointly by the Department of Defense and a major nonmilitary business corporation. In this writing, I shall relate my participation in the project, offer occasional comments on the Western Electric Co. texts (some parts of which were based on an article I wrote for a technical journal), and inject a few highlights not otherwise explained.

PROTOTYPE OBJECTIVES

Department of Defense had set a demanding schedule. It required that a prototype installation be in operation in the Arctic by year-end 1953 so that operational testing and evaluation could be done in 1954.

Barter Island (Kaktovik) Alaska, BAR Main, the prototype site.

The arctic test location was to be at Barter Island (Kaktovik), Alaska, where the Air Force had a weather station with a good airstrip. To meet the objective would involve site layouts (7); design development and procurement of electronics, building and antenna design, and procurement; delivery of everything to Seattle by mid-July for Arctic-bound convoy (U.S. Navy); offloading this freight on the north coast of Alaska; constructing all facilities; and installing electronic equipment ready for test. We actually accomplished all this by mid-November, six weeks early.

MOBILIZATION AND DESIGN

The Bell System was used to mobilizing task forces from its subsidiaries. I was invited to go to New York City the first week of 1953 to see if I would be interested in a special assignment (not explained) for a period of 6-12 months. It was there that I learned the nature of the project and that I was being offered the position of Building Engineer. I would be required to take temporary residence in New York City with trips home allowed alternate weekends. It was an intriguing challenge I was eager to accept and, with Marjorie’s concurrence, did accept. I started work about a week later, which was as soon as I could hand over my Michigan Bell responsibilities and get my personal affairs arranged.

In the beginning, the project office was in Western Electric Co. (WECo) Radio Division offices at 120 Broadway. I lived at the Roosevelt Hotel at Madison and 45th Street. From there I had easy underground access to the Lexington Avenue subway which had express service to lower Broadway. I worked six days a week except for (alternate) weekends home at Birmingham, Michigan.

At that time there was, in the U.S., very little technical reference material about arctic construction. At Pt. Barrow, the Navy had used only crude adaptations of surplus war material. The only text sources on permafrost were Russian and many had not been translated to English. On the other hand, our design consultants could draw on their 1951 experience at the Thule, Greenland AFB. One of our unknowns was about summer rain and lightning. In the absence of data, we provided lightning protection and waterproof construction joints. It was a good precaution – we needed them.

For buildings, we copied the type used at Thule. This sufficed for the test, but for later work we did a completely new, original design. The custom-made radar antenna was enclosed in a pneumatic radome. Other antennas were mounted on 80′ poles or 120′ towers of stacked scaffold sections. These types of shortcuts enabled us to meet scheduled deadlines. Final design effort was not to be undertaken until performance tests met DOD goals and Congress authorized the full project to proceed.

The scope of building engineering included buildings for equipment and personnel, soil mechanics and earthwork, garages for heavy equipment, fuel systems, and power generation and distribution. Other sections in the Project Office took care of site selection and layout (critical for proper functioning of electronic gear), and antennas and their supporting structures. As Project Manager, WECo did very little actual design work; rather, we supervised architectural and engineering design firms, all of whom had prior experience in the design of Air Force facilities at Thule. The Bell Telephone Laboratories did the design development for all electronic gear. They were also available for advice and testing of materials subject to arctic weather.

Immediately after lining up the NE team, we selected the Construction Contractor. Site selection was done in February by our Site Engineer crew who had gone north with the Contractor. They completed their layouts in March. Final details were expedited to New York City and by April were incorporated into the construction drawings. These, and foundation details, were then issued to the Contractor. The main station was at Barter Island. One auxiliary was 100 miles west at Bullen Point. The other auxiliary was 100 miles east just into Yukon Territory, Canada. These two auxiliaries and four intermediates were situated on barren tundra.

PROCUREMENT AND LOGISTICS

To save time and maintain control, the procurement of all construction material designed for the Project was done within Project Office. From the beginning, we required our NE design firms to prepare detailed bills of material as their designs evolved. Using this data, we developed a coding and marking system for each and every item procured and shipped. In a reiterative process, my expediters, together with purchasing agents in the Procurement Division, prepared lists to cover every item according to class of material and site destination.

The two construction companies that were chosen for Project 572 (the DEWLine). L to R: Beauvais, Clark, & Hemmings. Edmonton, June 1955.

The general construction contract was awarded to a joint venture: one firm with Alaska experience and the other who had previously worked for WECo. The Contractor had responsibility to determine his own office and on-site needs and to develop a logistic plan to support himself in the field.

MASTER SCHEDULE – 1953

The overall plan for construction operations had roughly seven phases.

- Contractor to establish project office in Fairbanks (space made available in Hangar No.1, Ladd AFB) and at Barter Island on the north shore.

- Air Force C-124 cargo planes deliver heavy equipment to Barter.

- Contractor to move available material from Pt. Barrow by cat-train on ocean ice and deliver to sites.

- Proceed with all earthwork, airstrips, foundations, and fuel storage to complete prior to sea lift.

- U.S. Navy to deliver all cargo and fuel on or about August 1, the earliest we could anticipate the Beaufort Sea coast to be ice free.

- Construct all buildings, antennas, and other fixed facilities before onset of winter storms.

- Turn over new construction to WECo Operations “radicians” to install electronic gear, take over housekeeping and self-support, and start tests.

CONSTRUCTION PHASE – 1953

The first construction was a mockup of electronic space for initial field testing. Four sites were leased between Streator and Rockford, Illinois. Work started in March and equipment was in operation before May 1. One of my engineers, Jim Thompson, was resident on the job, and I made two or three trips there.

The second item constructed was a receiving station in Anchorage. Work started on this in April, which was the earliest weather would permit. Building materials were expedited via coastal shipping and air freight. Thompson and another engineer went to Anchorage to oversee this work and report about problems which might need to be corrected. Communication was sometimes by phone, but mostly teletype.

By mid-April, the construction camps had quarters ready for WECo staff, and gravel hauling commenced. By placing 4′ or more of gravel on top of the ground in cold weather, the permafrost was stabilized and would remain frozen all summer. This gravel fill was essential for all roads, building pads, and airstrips. Two of my staff and one soils consultant took up residence to inspect this early work.

In mid-June, I was asked to go to Barter Island to provide oversight of the Contractor, to provide knowledgeable interpretation of plans and specifications, to assure orderly receipt and care of sea lift freight, to approve completed work, and exercise general oversight of the Contractor. My staff of about 20 included engineers and expediters from the New York office, technical people from the NE, and several inspectors from Bell operating companies.

Arctic living quarters.

We lived in insulated canvas shelters with kerosene stoves. We shared a common wash house with construction employees. Food was excellent. The construction force totaled about 600. We all worked 70-84 hours per week, sometimes more. Small planes were used to transport personnel, supplies, and food between Barter island and the six outlying sites. Communication by HF voice radio was inconsistent but adequate.

The sea lift arrived on schedule August 1, and the required preliminary work was in order. The next 72 hours of nonstop activity saw all cargo unloaded onto prepared beach sites. Our logistic plans for material identification worked to perfection. Out of more than 15,000 items, only one was unaccounted (later found in November). Receivals were so well organized that before the end of the second day material was moving from the beach to construction site in an orderly fashion. The system worked so well it was used for all future sea lifts.

Construction work completed ahead of schedule and we cleared out by mid-October and went home. Some of us returned to New York office in November to close out paperwork.

One interesting note: the first time the search radar was turned on in November, it detected a plane approaching from the north. It was undoubtedly Russian because upon receiving our radar signal, it approached no closer, turned around and vanished northward over the Arctic Ocean.

For the next eight months, USAF tested the new facility. All criteria being satisfied, USAF had Congress appropriate funds for the complete North American project and WECo was directed in September 1954 to proceed.

REDESIGN – 1954

The 1953 prototype system employed a lot of expedient designs in order to meet the tight schedule. Now it was necessary to evaluate all components and develop new and improved designs to meet higher operating criteria, to assure Arctic survival for 15 years, and to have all materials and components that could be produced and transported to the remote Arctic regions. Most of these problems had been studied during the test phase and many ideas for upgrade were under consideration.

In late September, I received the invitation to rejoin the project as Building Engineer. (All participation was voluntary: anyone could refuse without prejudice.) The term this time was to be at least two, probably three years. I agreed, provided I was authorized a home relocation to the New York area. I started working at 40 Worth Street in early October, returning to Birmingham alternate weekends. In early October, I signed a contract for a new “spec” house at 1 Cleveland Road, Summit, New Jersey. It was a standard four-bedroom, two-bath colonial with two-car garage at basement level. We moved the first week of January 1955.

During the redesign period, I had some of the 1953 WECo personnel working for me. Also, we had retained the same NE design team. Our new designs were for modular buildings to be constructed of wood to eliminate the source of static inherent in metal structures. Particular attention was devoted to heavy applications of fire retardant paint on all components. The power plants were adapted from standard Bell System specifications of proven reliability and electronic compatibility. Heat recovery from the generators and electronic equipment was so effective that it provided all the heat needed for all occupied space in the coldest weather (down to -70°F).

Other design work was addressed to garages, hangars, and fuel facilities. Concurrently, the project staff and Bell Labs came up with improved designs for electronic gear, radonics, and antenna structures.

While all this was going on, the Siting Team was busy in office and field selecting sites for the 57 arctic stations. The locations selected in Alaska and western Canada were fairly well identified during the testing phase. Not so for eastern Canada where selection was hampered by inaccurate, or total lack of, topographic maps. At many remote areas, siting crews had to be placed on the ground in mid-winter to electronically path-test proposed routes. Once a site had been selected, the exact location had to be determined by astronomical survey and the terrain mapped topographically. From this data, the Siting Team proceeded to layout for all facilities: buildings, antennas, airstrips, fuel facilities, and beaches for landing cargo. As it turned out, eight of the sites could not be reached by sea. All cargo for these locations had to come in by airlift.

CONSTRUCTION -1955, 1956, 1957 (Be sure to check out the photo galleries at the end of the article.)

At the end of December, I was promoted to Superintendent of Construction for the entire project, which extended some 3,000 miles from the west coast of Alaska to the east coast of Baffin Island. As the Contractors were gearing up and establishing “pioneer” camps at each site, my first task was to assemble a field staff of Bell System employees: one or two persons on each site. Our Personnel Department assembled a list of candidates who had expressed, at least tentatively, an interest in the arctic work. I was very busy for several weeks reading resumes and traveling around the country for interviews. In due time, I had 120 men to fill the jobs. These were supported by about 25 architects and engineers from our NE firms.

Just as I was about to make my first trip to Pt. Barrow, Alaska, I was confined to bed with mumps contracted from Bill who came down with them just as he arrived in New Jersey. Fortunately, my attack was not serious, and it held me down only about a week. For the next three years, I was away from home two-thirds of the time. My longest absence was two months: some trips were less than a week.

Except for trips on the Project USAF plane, my travel out of New York City was on commercial airlines. The principle destinations were Montreal, Edmonton (rear Contractor offices), and Fairbanks. From these cities I flew on the Contractors’ aircraft to the Arctic.

Arctic air travel. All the comforts of home.

These were usually DC-3, DC-4, or C-46 in cargo configuration with minimal passenger amenities. On the line, site-to-site travel was in a wide variety of smaller aircraft, such as Cessna, Norseman, Anson, Beech Bonanza, Beaver, military helicopter, as well as DC-3. Also, USAF assigned to the Project a long-range C-54 especially equipped for arctic service. It was based at Mitchell AFB, Long Island. This was piloted by two very experienced arctic pilots: Capt. Doug Radney (USAF) and Wing Commander “Squirt” Wiseman (RCAF) who was also the Canadian government liaison officer for the Project.

Wrecked C-124 at Cambridge Bay, CAM-Main.

Occasionally I could hitch a ride home from the line on a USAF C-124 (high-capacity, long-range cargo plane used for transport of heavy or large loads). Needless to say, much of the flying had a fairly high element of risk, but there was only one fatality among WECo and Contractor staff. A less sanguine statistic was the 15 or 20 men killed in crashes of both civilian and USAF planes. USAF lost three C-124 and one C-123 aircraft.

Most pilots actually liked flying best in mid-winter (January-April) because the cold air offered the most “lift” and the weather was usually predictably fair. Spring and summer were often foggy. Fall was stormy until the bodies of water froze and could produce no moisture for snow. Summer temperatures were usually in the 35-60 °F. range but would sometimes rise above 70 (accompanied then by mosquitoes). Snow melt occurred early May to mid-June. Much of summer was foggy. Winter onset was in September. The highest winds occurred in October and November, often of hurricane strength, but the normal velocity was about 15 mph and usually consistent in direction for each site. The coldest I experienced was -72 °F. The severest wind was a three-day November blizzard with continual winds 80-100 mph at a site on the McKenzie River delta.

Housing varied from insulated canvas Quonset-type shelters to tents to plywood buildings. The tricks to keeping them habitable were (a) bank the sides with snow blocks and (b) have a small fan to keep the air from stratifying. The heat came from a kerosene stove. Each sleeping hut had a wash basin. A central wash house took care of showers and laundry.

The work in Alaska was essentially complete in Spring 1957. Western Canada finished up ahead of schedule in June. Eastern Canada had to deal with very difficult terrain and the worst weather. Heroically, they were substantially complete by the due date of July 31, although some work continued for another six weeks.

Completion of field work saw me back in the office for final paperwork. In October, I attended a company management school. In November, instead of returning to Michigan Bell, I was transferred to Bell Telephone Laboratories in the position of General Plant Engineer (title changed later to Director, Plant Engineering). For the next 9-1/2 years, my office at the Murray Hill Lab was out two miles from my home in Summit, New Jersey.

The Markham Cheever Construction Photo Gallery

The following pictures are from Markham Cheever’s extensive photo collection and were selected for display because they depicted construction activities of some sort. The photos have been graciously provided by Markham’s sons, Paul and Will.

DEWLiner Paul Kelley, sorted, catalogued, and annotated the collection. The pictures shown below are but a small sampling of the collection.

For convenience, the pictures are sorted by Sector, from West to East, then by Site within the Sector, from West to East. Sites are not listed where there were no pictures showing construction activity.

Also, site-specific pictures have been posted at the bottom of each site’s page.

In November of 2019, DEWLiners Paul Kelley and Brian (Simon) Jeffrey completed the scanning and cataloging of the complete collection which can be seen here. The collection is hosted on line by Markham’s two sons Paul and Will Cheever.

POW Sector

- POW Main (Click on thumbnail to enlarge.)

- POW Main: Holes for the foundation for the Doppler tower. March 1956.

- POW Main: Loosening the clamps on the roof jig for module assembly. Feb 16, 1955.

- POW Main: Turning over a module floor after construction. Feb 16, 1955.

- POW Main: One of the modules still in its skids awaiting placement in the module train. Feb 1955.

- POW Main: Pouring the concrete foundation for wall support. Oct 1955.

- POW Main: The structure for the hanger being built. Oct 1955.

- POW Main: Starting work on the hanger roof. Oct 1955.

- POW Main: Working on the hanger roof. Oct 1955.

- POW Main: L to R, Ray Reed & Gail Wilson from WECO. June 1955.

- POW 1 (Click on thumbnail to enlarge.)

- POW-1: Module train and garage. The radome is not yet assembled awaiting installation of the radar antennas. Mar 1956.

- POW-1: Radome platform awaiting installation of the two radar antennas. Mar 1956.

- POW-1: Drilling anchors for the Doppler tower. Mar 1956.

- POW-1: Pile set for the Doppler tower footings. Mar 1956.

BAR Sector

- POW-3 (Click on thumbnail to enlarge.)

- POW-3: Markham Cheever (without his signature red cap) at the WECO office at Bullen Point (POW-3). Oct 1953.

- POW-3: Lewis and Markham in front of the WECO office. Oct 1953.

- POW-3: Typical heavy construction equipment. Sept 1953.

- POW-3: Job and airstrip. Sept 1953.

- POW-3: Beached landing craft at the side of the airstrip. Aug 1953.

- BAR Main (Click on thumbnail to enlarge.)

- BAR Main: View of the beach from the bow of a LST. Aug 1, 1953.

- BAR Main: Beach view. Aug 1953.

- MAR Main: Unloading one of the LST. Aug 1953.

- BAR Main: Beached LST. Aug 1, 1953.

- BAR Main: LST’s blown together by high winds. Aug 1, 1953.

- BAR Main: POL drum storage area on the beach. Aug 1, 1953.

- BAR Main: LCU approaching the beach. Aug 1953.

- BAR Main: LCU unloading poles. Aug 1953.

- BAR Main: Unloaded cargo on the beach awaiting transportation to the main site. Aug 1953.

- BAR Main: Pilings at the east side of the S1 building. Mar 1956.

- BAR Main: Setting pilings for building supports. Mar 1956.

- BAR Main: L to R, Williams & Winchester with a fog bank in the background. Sept 1953.

- BAR Main: Site view from the Doppler tower. Mar 1953.

- BAR Main: A Hy-Lift handling cargo in ship hold. Aug 1, 1953.

- BAR Main: Hanger frame in the distance with a DC-3 overhead. Mar 1956.

- BAR Main: Construction camp. Living quarters for the workers. July 1953.

- BAR Main: Camp and airstrip. Aug 1953.

- BAR Main: Snow drifts on the POL tanks. Mar 1956.

- BAR-A (Click on thumbnail to enlarge.)

- BAR-A: Approaching the landing strip. Aug 1953.

- BAR-A: The Doppler tower holding the two antennas, one aimed east and the other to the west. Aug 1953.

- BAR-A: Left to right, Abernathy, Blevins & Knight. Aug 1953.

- BAR-A: Paul Marsh pulling coax cable up the Doppler tower. Aug 1953.

- BAR-A: Inspecting the floor in the Electronics Module. Aug 2, 1953.

- BAR-1 (Click on thumbnail to enlarge.)

- BAR-1: Pouring the anchor for the Doppler tower. June 22, 1956.

- BAR-1: Breaking up camp. Oct 1953.

- BAR-1: L to R, Heuser, Bulton, & McAbee. Module construction in background. Aug 1953.

- BAR 1: Site is beginning to take shape. Aug 1953.

- BAR-1: One lonely site. Aug 1953.

- BAR-2 (Click on thumbnail to enlarge.)

- BAR-2: A C-124 delivers a much needed D-6 Cat. Mar 1956.

- BAR-2: West end of the module train sitting on pilings. June 23, 1956.

- BAR-2: Typical snow drifts against the module train. Receiving doors on the right. Mar 1956.

- BAR-2: Typical winter blizzard conditions. Nov 1955.

- BAR-2: What happens when you don’t close the truck door tight! Nov 1955.

- BAR-2: Markham Cheever holding a black fox skin. Mar 1956.

- BAR-2: Removing obstacles from the culvert. June 23, 1956.

PIN Sector

- BAR-3 (Click on thumbnail to enlarge.)

- BAR-3: Aerial view. Mar 1956.

- BAR-3: Another aerial view. July 1956.

- BAR-4 (Click on thumbnail to enlarge.)

- BAR-4: Aerial view looking North. July 9, 1956.

- BAR-4: Military C-124 unloading a much needed D-6 CAT and a 60KW generator. May 4, 1955.

- PIN Main (Click on thumbnail to enlarge.)

- PIN Main: Winter aerial view. Oct 1956.

- PIN Main: Summer aerial view. June 1956.

- PIN Main: Building the airstrip. Aug 26, 1956.

- PIN Main: Erection tent. Module train is at left. Mar 1956.

- PIN-A (Click on thumbnail to enlarge.)

- PIN-A: Old ice airstrip with the harbor in the background. June 22, 1955.

- PIN-A: Landing craft used to ferry supplies ashore. Aug 1955.

- PIN-A: Unloading the LCM. Aug 1955.

- PIN-A: Site’s module train and eventual home for 5-people.Aug 22, 1956.

- PIN-2 (Click on thumbnail to enlarge.)

- PIN-2: Frame for the hanger.May 23, 1956.

- PIN-2: Shop tent. Randy Wills on right. May 1955.

CAM Sector

- PIN-3 (Click on thumbnail to enlarge.)

- PIN-3: Getting ready to haul the modules onto the foundation to form the module train. July 1953.

- PIN-3: The module train before the radar antennas and radome have been installed. Mar 1956.

- PIN-3: High noon!. The two radar antennas and the radome have yet to be installed. Jan 1956.

- PIN-D (Click on thumbnail to enlarge.)

- PIN-D: Aerial view from the South. Mar 1953.

- PIN-D: Aerial view from the Southwest. July 10, 1956.

- CAM Main (Click on thumbnail to enlarge.)

- CAM Main: Summer resupply. Unloading at 2300 hrs. Still light. Aug 20, 1956.

- CAM Main: Summer sunset at 2300 hrs. The sun never really sets. Aug 20, 1956.

- CAM-1 (Click on thumbnail to enlarge.)

- CAM-1: Fabricating the radome trusses Oct 1955.

- CAM-1: Wrecked and abandoned military C-124. Oct 1955.

- CAM-B

CAM-B: Water filled excavation where the base for the Doppler tower will go. June 1956.

- CAM-2 (Click on thumbnail to enlarge.)

- CAM-2: Heating concrete and gravel. Oct 1955.

- CAM-2: Modules being organized prior to final assembly. Oct 1955.

- CAM-2: Module train under construction. The radar antenna platform has yet to be constructed. Oct 1955.

- CAM-2: Module train under construction. Closer view. Oct 1955.

- CAM-2: Finished garage. Oct 1955.

- CAM-3 (Click on thumbnail to enlarge.)

- CAM-3: Sunbathing. Catch some sun while you can! June 26, 1956.

- CAM-3: Welding 2″ POL pipes on an oil-drum sawhorse. July 12, 1956.

FOX Sector

- CAM-4 (Click on thumbnail to enlarge.)

- CAM-4: Markham Cheever (with his red cap) at the end of a successful fishing expedition. Caught 3 trout in 15 minutes. Aug 8, 1956.

- CAM-4: Aerial view. Sept 16, 1956.

- CAM-4: The living quarters at the construction site. Mar 1955.

- CAM-E

CAM-E: Roll of Stryoflex cable trench to the garage. The person in the middle is most likely Markham Cheever (red cap!). Aug 9, 1956.

- CAM-5 (Click on thumbnail to enlarge.)

- CAM-5: Sept 23, 1956. C-46, CF-IHR overran the runway. May 3, 1957.

- CAM-5: Aerial view. Lonely looking site! Mar 1956.

- CAM-5: Another aerial view of the site. Mar 1956.

- CAM-5: Paul Fletcher outside the module train.Mar 30, 1956.

- CAM-5: Road construction to the airstrip. May 8, 1955.

- CAM-5: View from the South. Mar 1956.

- CAM-5: View of the module train from the South. Mar 1956.

- CAM-5: Site view from the road to/from the airstrip.Mar 30, 1957.

- CAM-5: Module train prior to the radar antenna platform being constructed. Mar 19567.

- CAM-F

CAM-F: Aerial view of the Doppler antenna. July 12, 1956.

- FOX Main (Click on thumbnail to enlarge.)

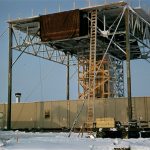

- FOX Main: 60′ lateral antenna facing West. Aug 19, 1956.

- FOX Main: 60′ lateral antenna in the foreground with the Doppler and IS-101 antenna array in the background. Aug 27. 1956.

- FOX Main: Installing the roof panels on the garage. Oct 1955.

- FOX Main: Garage doors being tested. Oct 1955.

- FOX Main: DC-3 airlifting material to FOX Main. April 13, 1955.

- FOX Mail: Material storage area. Oct 1955.

- FOX Main: More material in storage. Oct 1955.

- FOX Main: Cold storage (very cold!). Oct 1955.

- FOX Main: Radome construction as seen from the Doppler tower (mid point). Aug 8, 1956.

- FOX Main: Radome construction as viewed fro the top of the Doppler tower. Aug 8, 1956.

- FOX Main: Ground view of the radome construction. Aug 8, 1956.

- FOX Main: Close-up of the radome construction/erection. Aug 8, 1956.

- FOX-Main: Radome construction form the inside. Aug 8, 1956.

- FOX-1 (Click on thumbnail to enlarge.)

- FOX-1: Beach operations. Aug 30, 1956.

- FOX-1: laying the foundation for the module train. Nov 1955.

- FOX-A

FOX-A: Aerial view. Soon to be home for 5-people. Mar 1956.

- FOX-2 (Click on thumbnail to enlarge.)

- FOX-2: Erection tent. Nov 1955.

- FOX-2: Forms for the radome anchors. Nov 1955.

- FOX-2: Para-dropping a D-4 CAT. Mar 31, 1955.

- FOX-2: Aerial view of the future home for about 15-20 people. Apr 1956.

DYE Sector

- FOX-D (Click on thumbnail to enlarge.)

- FOX-D: Aerial view. Oct 11, 1956.

- FOX-D: Rime ice on the foundation. Sept 1955.

- FOX-D: Rime ice on the living quarters. L to R, Scoville & Galli. Swpt 1955.

- DYE Main (Click on thumbnail to enlarge.)

- DYE Main: Aerial view of the Upper Camp. Aug 27, 1957.

- DYE Main: Another view of the Upper Camp. Aug 27, 1957

- DYE Main: Photo of the Upper Camp modues showing the two module trains and the interconnecting ‘bridge.’ Aug 27, 1957.

- DYE Main: Hauling material from the beach to the site. Apr 1956.