Even More saga’s, Tales, & Lies.

Unlike the Memories section, War Stories are subjective, often amusing, sometimes larger than life, or just plain interesting anecdotes that DEWLiners would share with one another, if they could, over a beer (or two) on a Saturday night at the bar.

Be sure to visit the Memories section for a series of objective essays containing facts and information pertaining to the DEWLine itself, its history, places, equipment, living conditions, and personal experiences that speak to life on the Line.

CONTENTS

- DYE-4: First Radome Destruction, 1963 By Ed Marg

- DYE-4: The Puppies By Ed Marg

- DYE-4:The First Russian to Cross the DEWLine By Ed Marg

- DYE-4: THE Phantom Barber By Ed Marg

- DYE-4: Dog Attack By Ed Marg

- DYE-4: Bear Attack By Ed Marg

- DYE-4: The Bar By Ed Marg

- PIN-2: The ‘Swimmin’ Hole By John Hallier

- Early Warning in Action By Ron Turner

- Marconi in FOX Sector

- DEWDrop Memories By Emil Dusio

- Morale Check By Ed Marg

- My First Sighting of BAR-E By R. E. (Bob) Heath

- Life at DYE-1 the Pork Chop Dinner By Heinz Rengel

- It’s Really a Small World By Ron Blessin

- A Busy Day at Hall Beach “International” Airport By Paul Kelley

- DEWziak: A DEWLine Faux Pas By Paul Kelley

- Traffic at 12 O’clock High By Paul Kelley & Gary Naylor

- My DEW Line Console Operator Training Experience, Streator, IL, 1976 By Fred Teeter, Jr.

- DEW Line Personnel Politics & Then Some, 1976-77 By Fred Teeter, Jr.

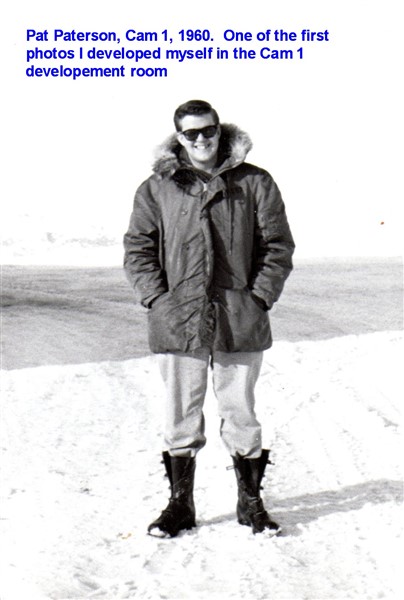

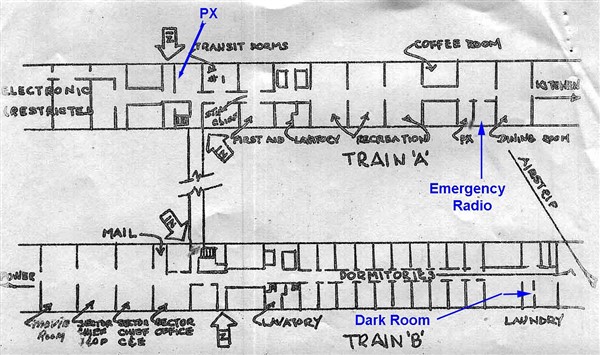

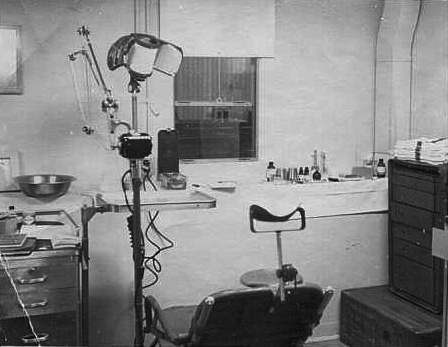

- The Case of the Oversized Breast By Pat Paterson

- DEWLine Dentistry By Paul Kelley

- May Day at PIN-4 By Steve Shewchuk

- The Mystery Norseman by Paul Kelley

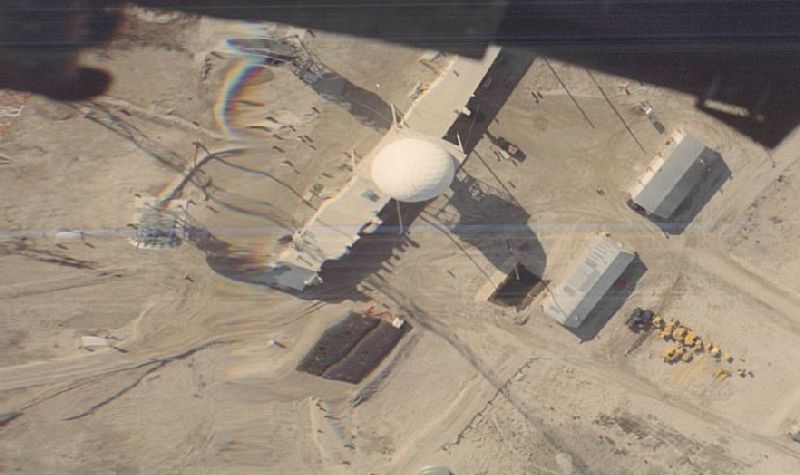

DYE-4: FIRST RADOME DESTRUCTION, 1963

By Ed Marg

I can’t be sure of the date, I believe it was May of 63. I was on duty , the wind was howling and the anemometer was holding steady at about 100 knots and intermittently pegging to 120 knots. We were watching the scope and then things started to happen. The sweep went to zero degrees and stopped, we were stunned, I have never seen that before. I had picked up a bit of trivia in school at Eglin AFB. There is a pin in the pedestal at zero degrees that is used for calibration purposes. I told my partner about this and said I would climb the stairs up to the radome and check it out. We thought that with the high wind and vibration it might have dropped in and stopped the antenna. I got to the top of the stairs, and the door leading out on to the antenna platform had a small window and pressed against that window was fiber glass parts of the radome. Anybody who opened that door was a dead man. I went back down and told my partner what had happened. Because we now had a gap of 200 miles of open ocean between Greenland and Iceland in the North American Air Defense line we concluded that we should send a coded message to “DATA” the military controller at Dye Main. We coded up the message and called Data and told him we had a message for him on the private line. Of course everybody in the Dye sector heard that and inevitability plugged into our private line. Anyhow, an hour after I sent off that secret message, the phone rang, and it was UPI wanting to know if we were going to evacuate the site. I could not believe my ears, was UPI reading our code, how could this be. I told him I had no idea of what he was talking about, and to call Sonde-strom, maybe they knew something. About 5 minutes later the phone rang again, this time it was the local newspaper in Paramus New Jersey. (Corporate headquarters). I gave him the same run-around. I don’t have any facts to back this up, but taking a wild a_ _ guess, I think someone on our site called the sector superintendent in Sonder-strom and told him what had happened over an open line, and he in turn called Paramus, and someone there, in their infinite stupidity called the press. Remember the time frame, the Cuban missile crisis was going on (damn near WW III)

The station chief who I believe was a retired navy corpsman, decided that we were going to evacuate down to the garage, we were to put on our arctic gear and assemble in the mess hall. The plan was to tie a rope around each one and trek on down the road to the garage. I went and sat in a corner and thought that if he tries to force me out the door I would shoot him. I think there were others who disagreed with his plan, so he procrastinated and after about 5 or 6 hours the winds started to die down.

This is when I found out that the windows in the composite building had three panes of glass. An outer, middle, and inner. When the antenna came off the tower a piece of it bounced off the hill and hit my window shattering the outer, breaking the middle and made a small hole in the inner, about one centimeter in diameter. Enough snow blew through that hole to fill a 55 gallon drum.

A month or so later, an Air Force full bird colonel came to investigate the security breach. He questioned me and my partner extensively, but we had done everything correct. Every thing was logged correctly, we used the right code book etc. They could not hang a peon with the security breach and every body else was retired Navy, so I think they let the whole thing drop. It was forbidden to take pictures of the damage, ( but I took one this one anyway).

(Click on photos for larger version.)

- Before the storm, with a radome.

- After the storm. Radome (and antenna) are gone!

DYE-4: THE PUPPIES

By Ed Marg

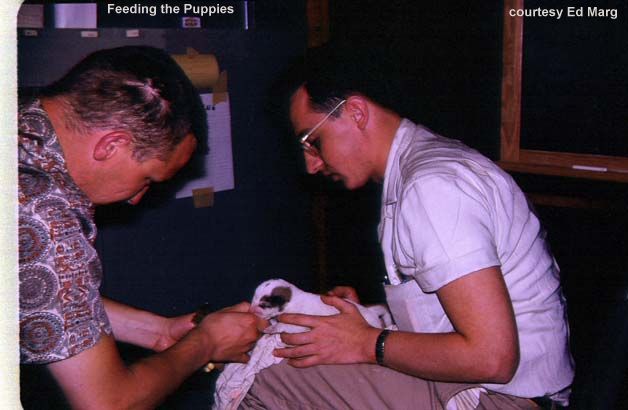

The tower for the radome had an elevator shaft that went to the top floor of the tower. The elevator was really a cage with a plywood floor that was raised and lowered by a power driven chain hoist. We stowed the cage on the first floor so that the ground floor was accessible. Some how a pregnant dog got into the elevator shaft and gave birth to nine puppies. We all went and saw the puppies, they were kind of cute, and seeing how they weren’t bothering anybody, it was decided to leave her there. One day a radician had the garage door open, it was spring time and a nice day. The mother decided to go out, and as she was leaving the radician decided to close the door behind her. The garage door was a chain, power driven roll up type. And as soon as the mother saw that she was about to be separated from her pups she tried to get back inside. The radician could not stop the door closing in time and it hit her on the back. She died the next day.

We now had nine puppies to look after. We tried feeding them with an eye dropper, but that didn’t work. We then tried the latex glove approach, that worked, but it was a two man job, one to hold the puppy the other to hold the glove and squeeze it. This would have worked except that it took almost three hours to feed all nine puppies. By the time we were finished, it was time to start all over again. We did this in shifts for a few days. Then someone spotted another dog on the side of the hill that had seven pups, the same size as ours. You could not tell the difference between them. We thought that maybe we could get her to feed all of them, and then we would feed her and make sure that she got well fed. It worked out well, we built a dog house out of an old shipping crate and a chicken wire fence on the side of the composite building. Things were going good until the pups got to be about eight or nine pounds and about as big around as a three pound coffee can. They could then climb the fence. We thought they were going up the side where there was icicles coming down from the building and the wire fence. As soon as they got over the fence the other dogs would eat them. We tried every thing we could to keep them from climbing the fence, but one by one they were all eaten except one. She got big enough to defend herself. She also became some sort of an Alfa. Because she was allowed inside of the building and we paid special attention to her, I guess this put her a few notches up on the pecking order.

The way I see it now is that we interfered with mother nature. Had we left the dog on the side of the hill alone, I am sure that more than one would have survived adolescence, with both parents there to defend them. See photo below.

(Click on photos for larger version.)

- DYE-4 puppies.

- Feeding the Dye-4 puppies.

Ed Marg

DYE-4: THE FIRST RUSSIAN TO CROSS THE DEWLINE

By Ed Marg

The time frame was some time after the blockade of Cuba was lifted. The Russians started flying a TU 114 or a TU 144, I can’t remember which, to Havana Cuba. They would come down on Tuesday and come back on Thursday, how long this went on I can’t say. My EOC was near and to avoid becoming “Bushy” I decided to leave and go back to the land of green coke bottles and round door knobs.

The time was about 2300Z, I was on watch and had the message compiler all set and ready to go for Scandinavian Air Lines flight 935 west bound out of Copenhagen Denmark which was due any minute. SAS flight 936 east bound from Los Angeles crossed over our site every night at about this time. Then I got a radar paint, a little bit north of where 935 usually showed up and a little bit early. I resisted the urge to send the “Tell” right away, even though I knew it was 935. The second sweep showed a south bound track. My first thought was that there was something wrong with the radar. This had to be 935, there was nothing else out there. I had to wait for another sweep, I was beginning to worry. The third sweep confirmed it, he was heading south. I franticly started resetting the complier and calculating speed and direction. The fourth sweep proved it, he was heading south at 500 mph. I sent the initial report to “Data” our military controller at Dye Main. Dye Main came back with “Track 34, OSD cease tell”. (I don’t remember the actual track number, OSD means friendly by reason of Origin, Speed and Direction) He clearly thought it was 935 too and not paying attention to the direction of travel. I called him back and said, are you sure, he’s coming from the north heading south at 500mph, he’s anything but friendly. Oh my god, give me two minute tells. We continued tracking him and about five minutes later Data come back with, he is a Russian TU 114 going to Havana Cuba, his call sign is Special eight. Give me five minute tells. Roger that, five minute tells. A little later Special eight broke squelch on 121.5 with “Big Gun Control, this is Special eight, you will give me radar position report, over.”

“Special eight, this is Big Gun control, you are on the guard frequency, QSY to 122.2 over”

“Big Gun Control, this is Special eight, you will give me radar position report, over.”

“Special eight, this is Big Gun control, you are on the guard frequency, change frequency to 122.2 mega hertz over.”

“Big Gun Control, this is Special eight, you will give me radar position report, over.”

” I said to no one in particular “F_ _ _ em, I am not going to answer him anymore.”

“Big Gun Control, this is Special eight, you will give me radar position report, over.”

I looked around me and there were four or five radicians standing behind me. Word travels fast around a Dew Line station.

“Big Gun Control, this is Special eight, you will give me radar position report, over.”

Nothing

“Big Gun Control, this is Special eight, you will give me radar position report, over.”

Nothing

Then on 122.2 he came on with “Big Gun Control, this is Special eight, you will give me radar position report, over.”

“Special eight, this is Big Gun control, your position at time 2317Z is 67 degrees 17 minutes and 32 seconds North, 35 degrees 17 minutes and 27 seconds West. Over.”

Five minutes later he came back again for a position report, which we gave him. Some one behind me said the navigator must be having a problem. We are used to dealing with SAS 935 and 936, they never ask for a position report, but we give them one anyway, just to have something to say and break the monotony. For some reason we took an instant dislike of Special eight. I don’t think it was because he was the enemy, I think it had more to do with his use of the English language. It is something you realize later. He wasn’t asking for position reports, he was telling us. I suppose we should cut him a little slack, because he was translating from Russian to English, but we didn’t.

He progressed down the side of our scope about 50 miles east of us, down the strait of Denmark. He was about 180 miles out when he started asking for position reports again. We gave him two or three, and then some radician behind me said, “He’s trying to determine our range”. On the wall behind us is a Jet Navigation Map of Greenland, they immediately started plotting his course on the map, the plan was to keep giving him position reports as long as we could hear him. This is what we did until we lost contact with him about 50 miles outside of our radar range. We thought the Russians must be really screwed up, a simple radar receiver on board would have told them every thing they needed to know about our radar, range, PW, PRF etc. the FPS 30 was supposed to be a copy of a Russian radar (meant for clandestine purposes no doubt). It had a pulse width of 52 micro seconds with a peak power of 5 mega watts (I think it was 5 mega watts, but I am not sure). The normal pulse width of an American set is about 4 micro seconds with a peak power of 1 mega watt. With the FPS 30, you could throw an orange into the air thirty miles out and we would see it.

When I think back now about the Dew Line and of the men that manned it, the time, the energy, the hours watching the scope, the cost of construction was it worth it? Hell yes I say, we negated the Russian bomber force, they could no longer use it as a first strike weapon. They had to go to something else. Rockets and submarines which they could ill afford, and it eventually broke them. My sincerest congratulations to the men of the line, Well Done.

Ed Marg

DYE-4: THE PHANTOM BARBER

By Ed Marg

I read the story from the radician from Dye 2, and I am here to tell you that the phantom barber originated from Dye 4.

It started when someone passed out at the bar. In those days when someone passed out at the bar, we just left him there to sleep it off, after all, where else could he go. The phantom would take a chunk down the middle or down the side or a side burn or a mustache he even got someone’s eyebrow. After a while guys would make it back to their room before crashing. But that didn’t help either, the phantom would just go into his room and get him while asleep in bed. If you remember, there were no locks on the doors. I had a way of locking mine, I simply drilled a hole in the bolt between the door and the door jam and inserted a nail in it.

At first it was rather funny, guys would come down to the mess hall in the morning for breakfast with blotches of hair missing or with half a mustache. After all in a few weeks it would all grow back. But it just kept continuing, and it got old fast. Then we started hearing about it happening on other sites and we thought it must be a traveling radician, but we knew who was coming in and out and the times did not coincide with the events. So we concluded they were copy cats.

Pretty soon just about every body fell victim to the phantom except three of us. And we were high on the suspect list. We pointed out that the phantom might cut his own hair just to avoid suspicion. As I recall there were not any Dane’s that got their hair cut, it could have been one of them, but then I would think he would have done one of them to avoid suspicion. I am sure it was a radician.

Come to think of it, the guy who lost an eyebrow is high on my list, although I can’t remember his name. Your eyebrow’s are the most sensitive part of your body. I don’t care if you are fully passed out, someone touches your eyebrow your going to react. The only thing more sensitive is your eye lashes. We never found out who was doing it, but I can tell you this, if we had caught him we would have merrily beaten him to a bloody pulp and then sold his soul to the devil for the price of a used Yugo.

Ed Marg

DYE-4: DOG ATTACK

By Ed Marg

DYE 4 Incidents: I did not witness this or the following incident. They just happened while I was there.

A little background, Greenland is a territory of Denmark. Over ninety percent of the station personnel whose assignment was to maintain the station, cooks, mechanics, airfield maintenance etc were Danish. We did have four Danish radicians on our site. I think they were the only Danish radicians on the line.

In Denmark there are strict gun control laws. Its not that they could not have guns in Greenland, its just that, what were they to do with them when they went home.

One day, one of the Danish radicians was going down to the garage. As he was walking down the road, an empty dog sled being pulled by fifteen dogs went by him heading up the hill. He thought that was odd, having never seen a runaway sled before. They went past him for about fifty yards and then they turned around and came after him. He tried to make a run for it but did not make it. They caught him about a hundred yards from the garage. Fortunately for him he had on his parka and parka pants. As he went down he was screaming and yelling for help. He got one dog in a head lock and was punching him on the nose. The rest were biting him on the legs and arms. The Danes working in the garage heard the commotion and came to his rescue. They beat the dogs off with shovels. They then called the sheriff. The sheriff came out, found the dogs still attached to the sled and shot them all.

I never did find out how the dogs happened to be in this situation. I think what had happened was that the dogs were being hooked up to the sled and when the Eskimo left them unattended for a minute, they took off for the upper camp so they would not miss feeding time. The only person I have ever seen feeding the dogs was the cook who would throw them table scraps and leftovers. I think the dogs were just plain hungry.

Ed Marg

DYE-4: BEAR ATTACK

By Ed Marg

I had just got on the island, been there about a month, when the sheriff called with a medical emergency, and wanted to know if we could help. It seems a polar bear came on the island and attacked a small group of Eskimo women and children down by the lake. From what I heard, the kids were throwing snow balls at the bear trying to distract it so that the women could get away. But this one lady just was not fast enough. The bear took a swing at her and caught her on the top of her head and took her scalp off. What happed to the bear or how the Eskimos got away I don’t know. I imagine the Eskimos hunted it down and shot it, if it was still on the island. We sent for our supply plane from Sondrestrom (an Icelandic Air DC4, an old sucker, just barely able to get over the ice cap) and they took her to Iceland to the hospital there.

After she lost her scalp, it took about two hours for her to get to the sheriff, another two hours for the plane to get to Dye 4 and another two hours to get to Iceland. All and all about 6 to 7 hours before she was seen a doctor. From what I heard they took some skin from her butt and sewed it on her head. I don’t know if I believe that or not. I mean if you took skin from her butt and sewed it on her head, then her butt would have no skin. Whatever. She became somewhat of a minor celebrity in the village after that. Not so much for her near miss with a polar bear, but because she was the first Eskimo in the village ever to ride in the airplane. They see this plane land and takeoff every week and have no idea of how it can do that.

After that, every time I went outside, I went armed to the teeth. I had a Walther P38 and a Winchester model 94. They say that the only way you can kill a polar bear is to shoot him in the heart. Which is fine, if you know where the heart is, any place else and your just going to make him mad. My plan was to empty as much ammunition into him as I could and then run like hell.

In my entire time on the line, I never saw a polar bear.

Ed Marg

MARCONI IN FOX SECTOR

By J.K. Leslie

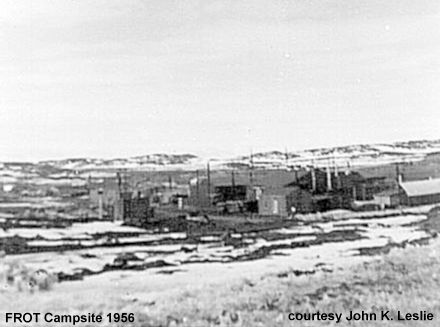

FROT

A small group of passengers strode from the hangar at Mont-Joli, P.Q. to a waiting Maritime Central Airways DC-3. Six or seven hours later we trudged in darkness from the airstrip to a hangar at Frobisher Bay (Iqaluit) (63.45’N; 68.33’W). Shortly, we would begin our contracts on the DEW Line with Canadian Marconi Company (communications), Foundation Company of Canada (construction), or Crawley and McCracken (catering). It was late autumn, 1956 and about -20C, not much colder than in Mont-Joli. We were 300 km south of the Arctic Circle, the southern limit of polar night, and 350 km from the nearest DEW Line station. Frobisher Bay was the staging-centre for FOX Sector, and as such, the largest settlement in the eastern Arctic (photo-1, below). Although it gained prominence during WW ll as an air transit point for war material bound for Europe, it was known to the Inuit centuries before explorer Martin Frobisher “found” it in late 16th century.

Photo-1.

We were ushered into the mess hall, and then shown the ‘bog’ and washbasins. A glance at the shower explained why it was used with trepidation, if at all. Two 45-gallon drums, one filled with ice-cold water and the other with scalding water, were side by side on top of a wooden cubicle. A normal shower was impossible, since in freezing conditions and catcalls from a queue of shriveling naked bodies an individual must adroitly adjust water flow to prevent being parboiled or frost-bound. Next, we were shown our temporary quarters, a Jamesway hut housing 20-30 double bunks. Forced air from a Hercules heater warmed the hut, from which odour from human bodies and cigarette smoke struck us when we opened the door. The main camp consisted of a cluster of temporary buildings on bleak, barren landscape (photo-2,below).

Photo-2.

Canadian Marconi’s (CMC) communications building was situated nearby on a low hill. Our arrival at the radio room met the stare of several savants engaged in deep dialectic debate over the relative merits of brands of beer. Veterans scanned us, no doubt wondering who would be the first to return south. Indeed, one of the newcomers fled within a few days. Several of the crew were awaiting posting to sites in FOX Sector whereas others were leaving FROT (site designation for Frobisher Bay) on R&R. After tiresome banter about the forestry of Baffin Island, they enquired if we were aware that our names had been broadcast on Radio Moscow shortwave bands. Passenger manifests were sometimes announced even before an aircraft landed at FROT. The announcer went by the moniker “Moscow Molly”, whose regular show was a popular feature for listeners in the North. But she would occasionally chide DEW Liners for abandoning family, friends, pets, and comforts at home, and remind us to expect ‘Dear John’ letters. Evidently, daily communication took place between Mont-Joli and Moscow, and in any case, our working frequency (5295 KHz) could be monitored in the Soviet Union. The thought that the DEW Line was a hopeless military adventure must have been common among workers, although articulation would likely mean job termination. Radio Moscow’s strong signals contrasted with fading, distorted broadcasts from stations in southern Canada. The fact that workers on a top-secret early warning radar line enjoyed “enemy” radio broadcasts undoubtedly provided the federal government impetus to establish CBC’s Northern Service in English in 1958.

The Canadian Marconi contingent consisted mainly of former military, merchant navy, and Department of Transport operators and technicians. During the construction phase, communication between sites was by means of Morse code. The transmitter at FROT was probably an AT-3 with 250-300W feeding an array of dipoles. The receiver was either a Hammarlund SP-600 or an RCA AR-88. The radio operator sat at a desk under a vent that brought warm air directly to his head. This was the most pleasant place in the radio room except when two Inuit general hands arrived to steam frozen contents of the honey bucket. Because we were obliged to remain at our desk during repeated spates of heavy traffic, we necessarily endured a nauseating stench for about 30 minutes. After a fortnight at FROT, I was assigned to Site 33 at Longstaff Bluff (68.56’N; 75.17’W). I thought I heard one of my cohorts say: “Wear the fox hat” or “Where in FOX that?” It was ‘Auxiliary’ site FOX-2, with a reputation for poor accommodation, an unpopular site superintendent, and relentless, savage storms. In addition, heavy communications traffic was assured. Thus, I wondered what wrath I had incurred to warrant this posting. Perhaps it was that direct question about operational protocol. I soon discovered that we were to “pound brass” for 12 hours without relief, control air traffic without radar or visual contact with the landing strip, take frequent weather observations, and run the movie projector following shift.

FOX-2

Site 33 consisted of two main camps, one near the shore and runway, and the other, where the modules were located, on a plateau ~100 m in elevation several kilometres inland. Rock debris littered the irregular terrain, with patches of snow in gullies. Blizzards were quite common, with wind gusts to 160 km/hr and minimum temperature of -48C, which I recorded in January 1957. Instances of ceiling and visibility unlimited (CAVU) were rare. Drifting snow was almost constant at the airstrip, although heavy snowfall was uncommon. The radio room, situated in the modules, contained an emergency HF transmitter (Collins 431-B) with an output of 1 KW and a Collins 51J4 general coverage receiver. An altimeter and anemometer indicators were fixed to a shelf in front of the radio operator. Excellent living conditions in the modules contrasted sharply with those suffered by CMC personnel. We occupied a small tent sparsely furnished with two cots, each with a sleeping bag, a coal oil stove for “heating”, and a urinal in the form of a metal trough thrust through the side of the tent. But what to do about number two? High winds or blocked feed line from the storage tank caused the flame to extinguish shortly after it was lit. It was therefore necessary to undress in a flash, or sleep fully clothed near ambient temperature. Since it was always as cold as charity, we used the tent only for sleeping. Further, extremely low humidity appeared to induce a mild form of sleep apnea, which affected my co-worker such that he was unable to complete his second contract.

There were numerous interesting characters at FOX-2, each with a set of reasons for working on the DEW Line. They were denizens of the lower camp, where the proletariat were housed. Most were lured to the Arctic by high wages and opportunity to save them. But tales were legion about returnees (or family and friends) who frittered away their “bundle” at home. And there were a few ‘Dear John’ victims who returned to the Line in despair. Others fled a marital imbroglio, or perhaps the law, whereas reclusive types cherished a simple life in relative solitude. A small number of fallen victims of barley fever hoped to escape their demon, since booze was prohibited on the Line.

Hopefully, at least one soul offered a simple “Thanks” to the pilot of IQR (dubbed “Arctic Rose”) prior to his final flight from the Line, for he was renown for selflessly serving personnel of the sector, even when blowing snow and low ceiling sometimes presented an especially dangerous situation for landing. A few Western Electric (WECO) boys failed to appreciate that weather conditions at airstrip and modules were not necessarily correlated. They greatly anticipated mail delivery, which could take two weeks to arrive from Montreal, let alone Texas or California. Propagation in late winter and early spring became problematic due to partial or total blackouts on HF bands, especially during Aurora Borealis. At such times nerves became frayed, since results did not meet expectations and messages stacked up. Boiling point was reached in mid-March, when during a blizzard, I advised IQR to overfly our station for reasons of safety. Henceforth, WECO crew changed my name to “Mud”, and man-made static in my communications receiver became unbearable. In late March, my humdrum life at FOX-2 took a turn for the better. Construction of the DEW Line was nearing completion and the operational phase was about to commence. A few WECO installers remained on site until supplanted by Federal Electric Corporation (FEC) radicians. Canadian Marconi closed operations at FOX-2, and I was transferred to FOX-D, an ‘Intermediate’ site.

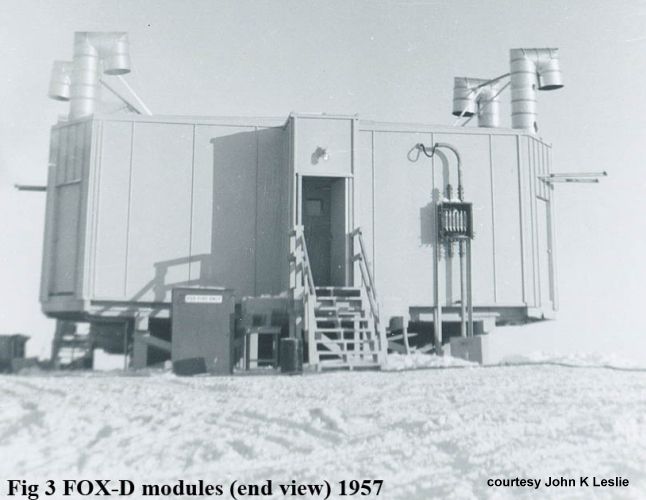

FOX-D

The Inuit camp at Kivitoo (67:56’N; 64:52’W) was located on the north shore of a fjord about 65 km north of Broughton Island (Qikiqtarjuaq). Modules at FOX-D (photo-3, below) were situated on a low gradient hill about 130 m ASL. The construction camp and airstrip (on ice) were located near the beach, whereas the CMC radio station and living quarters occupied a Jamesway hut (photo-4, below) at the base of the hill. We used a Bombardier to traverse several kilometers to the modules; the return trip could be accomplished in minutes by sitting on a slab of cardboard and coasting down the hill. Kivitoo, a former whaling station (photo-5, below) was abandoned in 1920, later resettled by Natives, then again abandoned in 1960 when the federal government relocated all Inuvialuit to Broughton Island. Weather and living conditions at FOX-D were much better than at FOX-2. Because poor propagation precluded HF communications, our operations ceased at the Jamesway hut. Nevertheless, my comrade, Harry George, and I fulfilled our contract obligations and maintained a 24-hour watch from the modules.

Click on photos for larger version.)

- Photo 3.

- Photo 4.

Photo-5.

Point-point communications to Auxiliary sites took place on VHF with a General Electric VO38 transceiver at 50-100 W. Aircraft were contacted with a Gonset air/ground VHF transceiver on 122.2 MHz. Regular meteorological observations pertained to conditions current at the modules, whereas pilots were given the weather that prevailed near the strip. Canadian Marconi was now an anachronism at FOX-D and our superfluity clearly reaffirmed one morning when Harry forgot to relieve me on watch. I would miss breakfast – again. During my downhill skid, I noticed an aircraft circling the airstrip. The pilot would be calling for landing information, I mused. I looked up the hill: impossible to reach the modules before the aircraft flew off. But it landed, thanks to FEC radicians in the modules, who provided all necessary data.

INUIT

We kept a small cache of emergency rations in our Jamesway hut in case of extended isolation during blizzards. Because our Inuktitut vocabulary consisted of only a single obscene word, we were unable to communicate with our hosts. Yet, when Inuit children stood statue-like outside our hut, we knew they came for any food we might provide – certainly not to admire two white CMC bods ugly enough to make a cat laugh. Tea, coffee, sugar, flour, and other non-perishables were received in silence and without expression. In the 1950s, Inuit relied totally on sled dogs for hunting various mammal species that sustain their families. The chilling reality of starvation was a constant in daily life, and loss of dogs could mean famine for all concerned. Such was the situation that faced one of the families at Kivitoo when its dogs, allowed to roam freely at the construction camp, were fed raw meat laced with Gillettes Lye. We then witnessed several victims in ghastly distress, wandering aimlessly with froth and frozen drool hanging from their mouth. This senseless, cruel act arose from frustration at failed appeals to the family to tether their dogs. That a member of the catering staff left FOX-D on the next available aircraft was no coincidence. The half-starved dogs had a history of tipping garbage bins set outside the cookhouse door, then ravenously devouring the spilled refuse. This resulted in debris spread over the immediate area. The young Inuk, now in middle age (in 2006), would undoubtedly recall this sad event. RCMP were never contacted and those of us who observed this barbaric act and failed in our duty, have had to live with our conscience. The fate of the Inuit family remains unknown. In May, Harry George and I departed FOX-D for the Mid-Canada Line. I later returned to the DEW Line as radician in the Western sector. Another story.

J.K. Leslie 2006

DYE-4: THE BAR

By Ed Marg

The Bar at Dye four was originally run by a radician named Bill, I forgot his last name. He was a real suave guy. He had a cleft lip (hare lip), but that did not seem to bother him any He was the type of guy that could go into a bar and the women would fall all over themselves trying to get to him. I never had that problem. Anyhow , he seemed to be in a pissing contest with the station chief, and one day the station chief caught him with an Eskimo in his room. He was fired and sent home. But when he got back to Paramus, he sweet talked them into a promotion and they sent him back to do some mods on the radar. But that’s another story. The problem now was that there was nobody to run the recreation committee. Me being the new guy and not knowing any better, they talked me into it. The rec committee consisted of me and four others who were there in name only. All they wanted to do was tend bar when they felt like it. What I inherited was a bar made out of two packing crates, 20 bucks in the till and a half a bottle of Cadillac Club (those of you who have been to Dew East will remember the taste of that stuff). If you remember, the recreation committee would buy all the beer rations (six cans per man per week) from the station PX and resell it over the bar for .25 cents a can. Guys coming back from R & R would smuggle a couple of bottles back with them, and we would sell that over the bar.

I went on a letter writing campaign to the whiskey and beer companies for free-bees. Coasters, swizzle sticks, glasses, signs etc, that’s when I found out there are only three different companies that make all the whiskey in the U.S. But they started sending all kinds of stuff. The cocktail glasses they sent were made of the cheapest glass. They had a fifty percent chance of surviving the dish washing machine. It was a real pain in the butt to have to clean out the broken glass from the dishwasher. So that after a while we just quit washing them and threw them away, we had so many. We had a closet were we kept bar supplies, and it was full from floor to ceiling with cases of glasses.

But the biggest coup of all was when I was playing with the telephone system. You remember how we used to dial into and out of each others PBX, go down the line and back and ring the phone next to you. Well I was fairly good at it, I managed to get the duty free store in Reykjavik Iceland. Well our supply plane was an Icelandic Air DC-4 that had to go back to Reykjavik every other week for maintenance, and he would stop at dye four on his way back to Sondrestrom fjord, Dye sector maintenance and supply facilities. It was also an Air Force Base and an international airport. I talked to the manager and asked him if he could put a package on board our supply plane when it was on its way back to Dye 4. He said he could, but that it would have to be paid for in advance and he would take a check. We ordered a case the first time of mixed brands at two and a half dollars a fifth. We now had all the booze we wanted.

Things were going along just fine, I can’t say that I had ever seen anybody go to work drunk. But I did see some that were so wasted I thought they would die, so did they. Our station chief was a gambler, I wish I could remember his name. He was the one T.T. Thorton took over from. He was actually playing the futures market from up there. He had a crap table set up in the bar, and was always ready for a game. I cant remember whether or not he had a Vegas style cover on it or not. But I do remember that he had a toy roulette wheel table that they used to play with big bucks on. About this time I managed to wangle a trip to Sondrestrom (to see the dentist) and while I was walking through the NCO club I was passing by an open door, and inside was a man working on slot machines. I went in and started talking to him. I asked him if would sell me one. At first he would not do it, but when I told him that it was for Dye four, he relented and let me have a nickel machine for two hundred dollars. From then on the rec committee never wanted for money. If fact just the opposite, the problem was how to spend it without throwing it away. We paid for every thing that you could reasonably say that the rec committee should pay for. Stuff for the gym, photo lab supplies etc. And then the Navy showed up with the sea lift supplies. They never stood a chance, with the station chief and his crap table and roulette wheel and the bar with its one armed bandit and free flowing booze, they went home broke.

Then one day the sector superintendent decided to take a little R&R in Iceland and was on board our supply plane on its way back to Dye 4. On board was the latest order for booze. Approximately 500 bottles, a little more that a thousand dollars worth. All wrapped in plain brown paper with my name on it. When the plane landed and the Danes started unloading, he said, what is all this stuff and who is Ed Marg. They said it was whiskey for the bar. My goose was cooked. The sector superintendent called me in and read me the riot act about drinking. But I pointed out that all the sites on the line had bars. He said that was for selling beer. I also pointed out that they sell booze to, if they can get it. But he got me with the coup de grace, he said I was smuggling from Iceland, a separate country to Denmark with out paying taxes. I told him I would quit doing it and resign from the rec committee. Which seemed to satisfy him, it did me, I only had a few more months before EOC. I appropriated a case of scotch of which I don’t think I ever drank more than a half a bottle. Remember in those days, it was macho to drink booze straight. I couldn’t do it then and I can’t do it now. The only reason I am writing this story about the bar, is because of JJ. Kizak DVD Dye Four disk one, there is a part where he has a shot of the “casino” and the slot machine. I think James got to Dye 4 about 15 years after I did, and the machine was still there. I know when I left, there was over $2,000 in the till and a huge supply of booze. I wonder what ever happen to it all.

Ed Marg

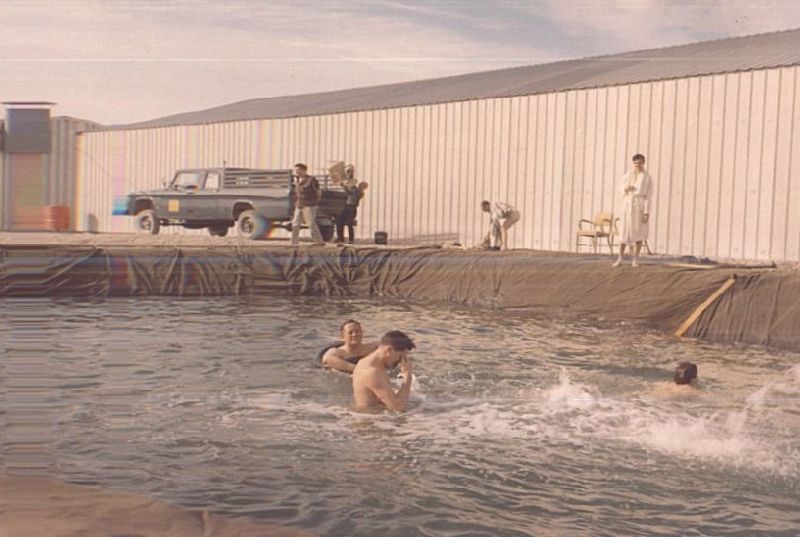

The PIN-2: THE SWIMMIN’ HOLE

By John Hallier

I served a brief tour of duty on the ‘Line in the early 1970s, first as a switchboard operator at Dye Main Upper Camp, then followed by a stint as Autolog Control Officer at Dye Main Lower Camp. Viewed at the time as a “get rich quick” scheme, I later wondered if I was really searching for my Father’s footprints having spent over 15 years on the DEWline in an assortment of tasks, the last being Superintendent DEWEast EWS circa 1972.

Most of my personal DEWline memories are as a boy growing up with a Father who’s work took him to distant places. My Father was a prolific writer who’s words never failed to enlighten and entertain. One of his more interesting tales had to do with the installation of an in-ground swimming pool at Pin-2 (Cape Young, NWT as it then was….) in the mid-1960s if I recall correctly.

Apparently they had a surplus auxiliary flexible fuel storage bladder that had either been damaged or was no longer serviceable as originally intended. A substantial hole was prepared well into the perma-frost that was located adjacent to one of the A-trains, and after some cosmetic surgery had been performed on the bladder, it was carefully laid into the hole as an impervious liner defining the shape of a large, rectangular swimming pool.

I believe I was on the threshold of my teenage years, and found Dad’s recollection of the event to be another example of a fascinating anecdote taking place at this almost mystical place somewhere I’d likely never visit.

Well that wasn’t to be the case. As a matter of fact, visiting this swimming pool at PIN-2 became an obsession of mine during the summer of 1968 when I finally arrived at the beach head at Cape Young as a member of the crew of U.S.N.S. Pinnebog, one of three World War II vintage Auxiliary-Oil-Gas (“AOG”) light tankers that supplied the coastal DEWline sites with their petroleum, oil and lubrication (“POL”) products.

Although the DEWline sites themselves were strictly off limits for all members of the crew at all times, wild horses could not have kept me away from verifying with my own eyes the existence of the most northerly located recreational swimming hole in the free world. I was one of three Ordinary Seamen aboard the vessel, and one of our tasks was to run the discharge hoses ashore in preparation for pumping, and we would ordinarily have three to four hours on shore until that operation was complete.

It proved to be an ideal opportunity for an Able Seaman and myself to wander off on a lightly veiled mission of discovery that ultimately found us in the shadow of the radome. It wasn’t long before our presence was discovered, and once proper introductions had been made, my shipmate and I were invited inside where we were then entertained in the site’s bar which had been conveniently opened in honour of the occasion.

Being the tender age of 18 years at the time, my onshore sea legs were in their infancy, and without too much insistence by those in attendance, my attempts to navigate safe passage to and from the washroom were heavily influenced by the all-too-many toasts to the Chief Clerk of the Sea ! Our jubilation’s were dramatically cut short that afternoon when a search party posse discovered our ship-wrecked souls with three sheets to the gale force wind and blown well of course as far as our Newfie Captain was concerned.

We plotted a perilous course through troubled waters as we made our way back to the ship that had patiently awaited our tardy return, and upon our somewhat unstable arrival on deck, we were both immediately ordered below and ordered to remain in our bunks until further notice.

We had anticipated a somewhat unfriendly reception at the ship, and had endeavored to prepare ourselves by loading the rims of our sea boots with cans of a versatile medical treatment that multitasks as a blood thinner and wound disinfectant when in its purified and undiluted form.

The frequent loss of can after can of our precious imbibing fluid resulted in a severe shortage of supply by the time we found ourselves safely below and out of harm’s way. The time spent sleeping did not adequately prepare my friend Tex or I for what we both concluded was harsh and unreasonable treatment by a vindictive Captain.

Each suffering the effects of a force 10 handover the following morning, we were advised that our chore for the day would be paint oriented, and we were presented with a five gallon pail of aluminum paint which had the consistency of water, two large whitewash styled brushes, and an armful of non-absorbent wiping cloths that would no doubt become necessary throughout the day.

We were then marched topsides to the ship’s single funnel, and were given instructions to paint the inside of this four story chimney while under weigh back to our home port of Tuktoyaktuk. USNS Pinnebog measured 315 feet at the waterline, and displaced approximately 3,500 net tonnes. Her main propulsion system was a twin screw, diesel-electric configuration with four 1,000 horsepower diesel engines each turning an electric generator that produced direct current that powered the two electric final drive motors attached to the propellers.

All exhaust pipes were ducted into the single funnel that was located directly above the engine room, and that contained an internal scaffolding of four levels of steel grate joined by a network of ladders and catwalks that provided access to the very top of the structure. I estimated the temperature to be well in excess of 120 degrees Fahrenheit at the coolest level, and I was even more surprised that we are able to continue breathing while experiencing such working conditions.

One can only imagine the degree of difficulty we encountered trying to apply a watery thin paint on hot vibrating surfaces such as those in the funnel. Each brush-full simply oozed down one’s arm and onto his body, and by the end of the ordeal, we both looked like we were auditioning for the part of Tin Man in the Wizard of Oz. We were covered from head to toe in aluminum paint and gallons of diesel fuel were consumed removing the material from our exposed flesh. Needless to say, both sets of clothing were destroyed after they dried to a crusty and rigid form.

In today’s world, such working conditions would of course be outlawed, and any seafarer who subjected a fellow seaman to such treatment would be flogged and keel-hauled to the delight of ship’s company. It was one hell of an experience, and in retrospect, I would have much rather taken a plunge in Dad’s rubber-lined swimming pool than the one I took that day in the bar. Mind you, hoisting a few to a romantic childhood memory seemed to be the right thing to do at the time, and I doubt I would change a moment of the event were it even possible !

Photos of the Swimmin’ Hole

|

|

|

|

In memory of my beloved Father, Jay Hallier, deceased.

John Hallier

Early Warning in Action

By Ron Turner

The following is from the lead-in to an early days Console Operations Training Manual. It was written in the 1950’s. The writing style was a little more dramatic in those days than today.

EARLY WARNING IN ACTION To watch and guard the airspace above 75,000 square miles of bleak and desolate Arctic tundra … to know of all airborne activity there … this is the Console Operator’s assignment. Sitting in the middle of the electronic nerve center and knowing his responsibility for so vast an area may well fill him with awe. He is aware that this nerve center’s vigilant eyes will “see” whatever is alien to that vast airspace. The tireless rotation of the radar sweeps on the PPI scopes reminds him those eyes are always searching. Their vision is almost perfect. Seldom do they fail to detect airborne objects entering the area. Watching the screen, the Operator sees what they see usually just an occasional friendly aircraft.

There hadn’t even been that much for Allan Fry one day last September at FOX-1. There had been a false alarm shortly after he had gone on duty. Other than that, nothing had been picked up on the scopes. Just a routine day: making the usual line checks, helping file a weather report, making log entries, and getting in a little OJT from a maintenance manual. It was almost time for the 2100 GMT entry: or, as Fry figured, 4 p.m. his local time. One more hour before finishing his shift. The relief Operator would be coming in soon and that would make the last hour pass a little faster, lessen the monotony.

The gong of the search radar sounded. A radalarm lamp flashed on. Fry jumped, involuntarily. Quickly he began taking the steps in the detection operation he knew by heart. He quickly marked the general area of the first blip. Another false alarm? Fry reset the radalarm and waited to see what the PPI scope would show on the next sweep. There it was a bright blip on the upper beam scope, closer this time. Fry began dialing his initial track report into the message composer. He turned the last position knob then made an estimate of the course, southeast. Finally, he pushed the button on the message composer to sent the message. He was thinking his sector Controller on the receiving end would be getting a break in his routine too.

While waiting for the Controller to check the pre-plotted flight plan position against his initial track report. Fry kept watching the scope. He began picking off additional data for his amending report. Speed over 600 knots. Altitude, about 50,000 feet. While pressing the transmit button, he mulled this over. At that speed and altitude, it couldn’t be a commercial airliner. The buzzer from the operational party line sounded. He reached over to the switch on his channel key. It was the controller telling him to try for IFF identification. No flight plan on record. Fry flipped the IFF toggle switch, and again waited. Nothing. He noticed his hands were beginning to sweat as he spoke into his mouthpiece, telling the Controller. “No response on IFF.” Contact the pilot. Fry tried to reach the pilot over the UHF air-ground radio. It was like talking to himself. He reported this to the Controller, who had no choice but to identify the plane as “unknown”. Lighting a cigarette, Fry began dialing his first follow-up report into the composer. Nothing changed except position, which showed the aircraft nearly overhead. As he reset the position dials, he was glad he had something mechanical to do while waiting further word from the Controller.

Art Mercer, the relief Operator, finally showed up. He had more news. A rigger at the station hangar had spotted the plane’s vapor trail. Was it one of those new turbojet Russian bombers they had heard of?

Twelve minutes had passed since the alarm first sounded. The two Operators were silent, intently watching the scope for new blips. Another five minutes ticked by. Then, out of the panel speaker came the controller’s voice. “some thing new on track KV62 … reclassified … faker.” Both men leaned back in their chairs, looked at each other, and grinned. So, it was a friendly plane that had flown over to test the alertness of the Line.

Ron Turner Alaska Radician 1968 – 1990

DEWDrop Memories

By Emil Dusio

Re: DewDrop

In 1959-1961 I was an Engineer with ITT Federal Labs in NJ assigned to DewLine Support for Federal Electric . In Oct 1960, two of us were dispatched to Dye Main to run EMI/EMC tests on a new building that would house comm gear with Thule. In Montreal we learned that the plane took cargo first and then passengers if they fit. Weather kept us grounded in Frobisher Bay for the better part of a week. In those days Frobisher Bay was an alternate landing site for trans-Atlantic flights . Amid the Quonset huts, there was a brick home with a white fence in the front that was the residence of the Pan Am? station manager and family. It looked like a direct lift from the Midwest.

Arriving at the lower camp we were informed that weather had delayed construction of the building, only the slab had been poured, and we would have to stay until Spring to conduct the tests. I disagreed and when told that I would be reported to my superiors in NJ I replied that I would be there alongside him. We could not get to the upper camp because the Generals were coming through and all resources were tied up for their arrival. Several days later when the plane came through again I was first on. Lee and I were married in January 1961.

It was short but I recall the trip as an important one in my life: I met men from the UK separated from family for 9 months at the time for the pay that would give their family a better life, the fire watch in our hut who wore half-Wellingtons and later I learned he was fired for sleeping on his watch, for the cat & tanker going out to the glacier to bring back ice for water, for the mechanics swapping a plane engine outside using a construction crane and getting reamed because they scratched something in the process. For the men monitoring the link via the submarine cable to Thule, knowing that the cable was broken.

Most of all for the dedication of these people to serve their nations.

Emil Dusio

Morale Check

By Ed Marg

There were two radicians at Dye 4 who had come up with a joke of sorts. One would get on the station PA (if my memory serves me correct, you could dial 21 on any phone on the station and get the PA) and say “Morale Check” and the other radician would shout at the top of his lungs “I hate this F—ing place”. It did not make any difference where he was or what he was doing. In the bathroom or the shower or on the console. He would shout it out at the top of his lungs. This went on for some time, five or six time a day. Every day, week in and week out. after a while it started to taper off. Maybe once or twice a day, and some days not at all.

It was during the summer, when the weather was nice, we started getting the tourist’s in (these are the people who had enough pull to get on the supply plane and visit a DEW Line site, so they can go home and brag about being on the line). It was on a Sunday, and we were sitting in the chow hall having coffee and Danish pastry (the real stuff). The supply plane had come in bringing the tourist’s, and sitting across from me was an Air Force major having coffee and Danish. Sitting directly behind him was the shouting half of the “morale check” joke. Over the speaker came “Morale Check”. He jumped up and screamed at the top of his lungs “I hate this f—ing place”, and sat back down drinking his coffee. The major turned and looked at him with a look of astonishment and wonder on his face that I will never forget, and then he looked at us, of course we had heard it so many times that we were immune to it and paid no attention. And that too astonished him. In fact he began to doubt what he had heard. His mouth sort of hung open as he looked around at the rest of us. I could tell what was going on in his mind, he wanted to ask us if we had heard it too. But he thought better of it, and continued to drink his coffee.

Ed Marg

My First Sighting of BAR-E in 1957

By R. E. (Bob) Heath

As I understand it, a lot of ice runways were constructed during the construction of the Dewline as a means to get construction equipment to a site until a suitable land runway could be built. BAR-E was the last site to be officially turned over from the construction contractors (Western Electric and Foundation Company of Canada) to the O&M contractor (Federal Electric at the time) and I was there at BAR-E in 1957 when it happened.

BAR-E was an especially difficult site because it’s about 500 ft Above Sea Level and no gravel was available anywhere near the site. However, copious quantities of gravel were available on the nearby seashore in the form of big gravel ridges. Thus, a tramway was constructed up the side of the seaside cliffs and the necessary gravel lifted up to “hilltop” level by cable car. Unfortunately, by the time I arrived at BAR-E the cable car operation was completed so I have no pictures of any of the apparatus used. More than likely the cable car rail line still exists; I expect that it was simply abandoned rather than any attempt made to dismantle it.

The Ice Runway, 1957.

Link to BAR-E page.

R. E. (Bob)Heath

Life at DYE-1: The Pork Chop Dinner

By Heinz Rengel

When I arrived at DYE-1 in the summer of 1966, I was introduced to Blacky and Lady. Two huskies that came over the icecap (dogsled) from Kulusuk to the west coast. Danish law prohibited them from going back (disease could spread) so they made themselves home at DYE-1 and the station personnel adopted them.

DYE-1, due to the terrain, did not have a runway but a 200 foot helipad and twice to three times a week Greenland Air would make a flight delivering freshfood, supplies and personnel to the station with their Sikorsky S-61. One day we received word that the Helicopter fleet was grounded due to a malfunctioning main rotor pitch control valve. One chopper had received damage upon shutdown at Gothaab and was out of commission.

We had fresh food for a few days and Sondrestrom told us that they would send us supplies via airdrop if the choppers could not be back in service soon.

In the mean time it was K-rations for us that the cooks managed to disguise in a variety of manners.

Then the day arrived of the Air Drop. Sondrestrom sent a Grumman SA-16 and while circling the site, they dropped the boxes of supplies. We were able to recover about 2/3 of the boxes, the rest ended up about 1500 ft down the northslope cliff with no way to retrieve them. The manifest listed all items shipped, among them 120 pound of pork chops, but they were missing from the boxes we retrieved.

Well, for about a week , Blacky and Lady could not be found and when they returned they were quite content. We just knew that they had found the missing boxes and helped themselves. So the pork chops did not go to waste.

After about 3 weeks the choppers were back in service and all was well. Below a picture of Blacky and as one can see, he looks quiet healthy.

Blacky.

It’s Really a Small World

By Ron Blessin

I served as a Radician and Main Station Supervisor in the PIN Sector from 1959 through 1962. It was during my stay at PIN-1 in late 1960 and 1961 that we had daily flights of B-52s fly by northbound and we would give them traffic and position reports as they went by. These flights were out of Fairchild AFB near Spokane, WA and had the radio call of “Kellogg followed by a number.” Jokingly, we started calling them “Corn Flakes” and established quite a camaraderie with the crews as they flew by. They asked what it was like on DEWLine and finally we said that if they provided us with an address, we’d send them some pictures of the site and its personnel. However, in return, we requested they send us some pictures of their aircraft suitable for framing. Since each site had a darkroom, we sent them over a dozen 8 X 10 inch pictures and a supporting letter with a description of each picture. A few weeks later, we got at least 6 air-to-air pictures of B-52s flying in formation and we mounted them on the walls of our recreation module. I wonder how long they remained on the walls and if anyone remembers them?

Now, let’s do a “fast forward” to January 2007. My wife, Ann, and I were on a cruise around the Horn of South America. I had attended a number of lectures by a retired US Army Colonel who was very conversant with the political situation in Chile, Argentina and specifically, the Falkland Islands War in 1982. He announced that he would be hosting a get-together of Military Service Veterans and, on a day at sea, I attended that event. There were at least fifty veterans from the U.S., British, a number of European mainland countries and I was the only RCAF veteran in attendance since I am originally from Chilliwack, British Columbia.

We were invited to give our name, branch of service and duties/postings during our military service. Seated a few seats away was a gentleman who said he had a 30-year career in the USAF flying B-52s up near the North Pole. He said he was stationed at Fairchild AFB and that he was the captain on “Kellogg” flights. I nearly lost my teeth. When my turn came, I said that I’d crewed in old Lancaster bombers based in Ottawa but then, as a civilian, I worked on DEWLine and I remembered those flights passing by. After the get-together was over, we sat down for a long talk. It turns out that he was the very Captain on the B-52 that we sent the pictures to and he mailed us the aircraft pictures that we hung on the wall. He remembered our calling his flights “Corn Flakes” and we enjoyed a good chuckle over it. On arrival home, I sent him a copy of my DEWLine documentary DVD to his retirement home in Texas. Having been 30,000 feet apart in 1961 in the arctic, we finally got to meet near the Falkland Islands!

What a small world.

Ronald Blessin

Springfield, MO

Af7a.ron@gmail.com

A Busy Day at Hall Beach “International” Airport

By Paul Kelley

On a typical day at Hall Beach (FOX Main) we only had two or three air movements by local aircraft – usually CF-IQD, Nordair’s trusty DC-3 servicing the other sites in Fox Sector. As it was now July the annual Sealift was in progress and with it the accompanying Airlift of supplies to the other sites in FOX Sector. With the airlift operating it was all change in terms of air traffic. We would have up to 8 aircraft (DC3’s and C46’s) operating almost 24/7 with 20+ movements a day. From the perspective of a console operator it was, relatively speaking, hectic, but fun. A pleasant change from watching not a lot for four hours.

I was on a two week cycle of day shifts (0700-1500) during this period and thoroughly enjoying myself. At some point the Military Commander passed the word that the Northern NORAD Inspection Party was scheduled to come through from DYE Main, stay a day and then depart for CAM Main and points west.

It was Monday, 10 July 1961, and I was on console duty when we were advised by DYE Main that the North Star had departed and would arrive at Fox Main about 2.5 hours later. Eventually I picked him up about 150 miles to the East and FOX 1 handed his track over to me. I was busy with about 8 aircraft coming and going at the time. Visibility was excellent but, in addition to the usual takeoff and landing interchanges with each aircraft, I undertook to ensure that each knew where the others were while enroute in and out of Fox Main. They were all experienced pilots and flying VFR in clear conditions wasn’t exactly the challenge of the month for them. However, keeping each aware of the others’ whereabouts seemed a sensible thing to do until they made visual contact, especially when two or more were likely to arrive at roughly the same time from different directions. I continued to track the North Star inbound from the East waiting for him to make contact which he did about 100 miles out. I had just finished with two takeoffs and two landings and had two more aircraft inbound from opposite directions. I could never hear myself but it must have sounded like an ATC centre of sorts and definitely not like FOX Main on a typical day. The reason I say this is that the initial call from our incoming guests was:

“Hall Beach International, Hall Beach International, this is North Star xxxxx, over.”

I had to chuckle. At last someone, however indirectly, had acknowledged the level of activity we were coping with. No one had made comment before and we just got on with it.

Suppressing the chuckle I replied and he made a few further comments about how busy we were, gave me his ETA and I gave him the local wind, altimeter and traffic situation. I just knew from his comments that we wouldn’t be getting any hassle from him re: procedure, squawking parrots (IFF), etc., – too busy to be playing games. I then just included him in my broadcast messages for the next half hour to continue ensuring that any aircraft near another had visual contact and then I could relax. They obviously had eyes themselves and were on the lookout but I just couldn’t sit and watch blips approaching one another without saying something – so I did, repeatedly.

The North Star landed without further ado and they began their inspection. That day and the next passed uneventfully and, on shift as I was, I saw little of them except in the dining room. In due course they departed to the West and that was that.

My first encounter with an RCAF Inspection and, from my limited perspective as a Radician, a total non-event, quite unlike my second encounter several months later

(see “MAYDAY at Fox-Main (Hall Beach)” WAR STORIES – VOLUME 1).

DEWziak: a DEWLine Faux Pas

By Paul Kelley

Northern NORAD, in Montreal, conducted periodic inspections of the Canadian sectors of the DEWline. What their precise terms of reference were I do not know but, to conduct their inspections, they required air transport which was provided by the RCAF Air Transport Command. They used a modified DC-4. In 1947 Canadair obtained a license from Douglas to build the DC-4 but they used Rolls Royce Merlin in-line, water cooled engines instead of the usual Pratt and Whitney radial engines to improve its performance. The Canadair version was called the North Star.

DEWziak – Ooziak

Apparently, when this inspection team was first established and assigned an aircraft they wanted to name the aircraft/flight with some sort of appropriate Inuit name – possibly a bit of early PR. Some wag suggested that “DEWziak” had a certain Inuit flavour to it and this was adopted. Little did the adoptees know at the time that an ‘ooziak’ was the cartilage or bone in a walrus’ penis! These things were in some demand and fetched a good price.

They were used for sundry pranks but the best one I heard of was told to me by the RCAF guys at FOX Main. One of them had bought two of them and used them as swizzle sticks for cocktails in one of the RCAF Officers Clubs. It made for many an interesting conversation with the young ladies escorted to the club by the members when they were apprised of what they were stirring their cocktails with!

A USAF C54, one of the original DEWZiak aircrafts from an earlier time.

Needless to say, it didn’t take much longer than usual for the upper brass of the inspection team to realize that they had become the laughing stock of the Arctic when they showed up in the aircraft with DEWziak emblazoned on it for all to see. It was quickly abandoned but I did find one reference to it in the DEWline training info handed out at Streator in late 1960 which meant that the ‘word’ had not yet penetrated that far south.

Traffic at 12 O’clock High

By Paul Kelley & Gary Naylor

Here’s an absolutely priceless story that came via Paul Kelley from Gary Naylor. The year was 1962 and Gary was one of the Military Controllers at FOX Main. He was on duty one day when Kenting Aviation’s B-17 Flying Fortress, CF-ICB, was out ‘mapping’ from altitude and a SAC B-52 was approaching from the South. Here’s the story in Gary’s own words.

“I left the Data Center and went into the Surveillance Room to look over the shoulder of the duty radician seated at the console.CF-ICB generally worked at 33-35000′ and the B-52 was at about the same altitude. I JUST KNEW that someday I would get to tell a B-52 to “Watch out for a B-17 traffic at 12 O’clock, 15 miles at 35,000 feet!” And I got the reaction I intended. Although I don’t recall the B-52’s exact words, he was definitely ‘surprised’.”

Kenting Aviation’s B-17 Flying Fortress at FOX Main. Courtesy Paul Kelley. August 6, 1961.

Paul’s observation: absolutely priceless and, I would venture to say, the ONLY time such an interchange has ever occurred. Thank you Gary. Special that.

My DEW Line Console Operator Training Experience, Streator, IL, 1976

By Fred Teeter, Jr., August 2015.

Forward: This article and a related piece (see next story) were composed to appeal to those unfamiliar with the DEW Line. I apologize to veteran DEW Liners who may find the narrative basic and technical details in error. I left the Line in 1978. It was long ago. I’m glad I kept a journal and grateful that I remember as much as I do. Enjoy.

It was 1976. I was a 22-year old college senior, building an English degree. I had no resume, no discernible skill, no clue. In an economy fried in OPEC oil, I was employment toast.

I took a call at the fraternity house. It was Uncle Rodney Gray, president of FELEC Services, Inc. FSI had won an operations, maintenance and supply (OMS) contract for the Distant Early Warning System (DEW Line), a string of arctic radar stations stretching from the West coast of Alaska, through Canada, to the east coast of Greenland.

“Do you want a job?” he asked.

“What and when?” I blurted excitedly.

“It’s remote,” he cautioned. “Most employees are retired military. They prefer work like this. We never recruit people your age.” I didn’t care. I needed a job.

“The title is ‘Console Operator’. It’s a new position.” I said yes.

I trained that summer at the DEW Line Training Center in Streator, IL. On the evening of July 11, I checked into the Plumb Hotel, a flophouse that survived only by housing DEW Line recruits. My third-floor daytime view of the street was okay. The nightly cacophony from the bars wasn’t. My small fan was good for white noise, bad against swimmable humidity. A communal bathroom with a shower was down the hall.

At 8:10 the next morning, a van shuttled our class of ten 15 minutes to the Training Center. The fenced-in compound held a radome and military huts and was surrounded by corn. Lead Trainer Tony Hendrickson oriented us at 8:30. A humorless older Canadian whose name I forget taught weather observation & reporting. The only textbook was MANOBS (Manual Observations), a venerable Canadian publication. Other class material consisted of photocopied handouts.

Classes ran 10 consecutive days. On most mornings before breakfast I ran a mile or more around a nearby park. Each evening, while I typed notes and studied handouts, my colleagues toured taverns. Most of Streator’s working population toiled 24-7 at a large DOW Corning factory. ‘Miller Time’ was anytime. When folks didn’t drink, they visited churches nearly numerous as bars.

We broke for a long weekend on July 22. I drove a rental to see my Indiana girlfriend. Classes resumed July 27.

Our written exam took place on August 3, from 2 p.m. to 4 p.m. I managed 84%. After dinner and a nap in town, we returned to the Center for the first of a two-part ‘practical’ exam taken at a mock console. From midnight to 7:30 a.m., Tony and his colleagues ran us through every scenario we might encounter on the Line. On Thursday, August 5, we repeated the process, adding weather observation & reporting. I copped a combined 81% on the practical.

Back in town, we opened a bar as the Sun came up. Canadian classmate Don Webb confessed to dropping LSD before starting Part 2 of his test. Don was the smartest guy in class, with the highest grades. He figured correctly that he could pass the course even if he failed the final. Navigating electromagnetic interference on the radar screen was a special pleasure.

A class in First Aid ended our training the morning of August 6. I departed Streator the following morning, ready for my experience of a lifetime.

DYE-4 Console, AN/FSA-26. Courtesy Fred Teeter Jr..

DEW Line Personnel Politics & Then Some, 1976-1977

A Personal Recollection.

By Fred Teeter, Jr., August 2015.

Forward: This article and a related piece (see above story) were composed to appeal to those unfamiliar with the DEW Line. I apologize to veteran DEW Liners who may find the narrative basic and technical details in error. I left the Line in 1978. It was long ago. I’m glad I kept a journal and grateful that I remember as much as I do. Enjoy.

In 1976, my senior year at college, Uncle Rodney Gray hired me to fill a new position called Console Operator on the Distant Early Warning System (DEW Line). Gray was the new president of FELEC Services, Inc. (FSI), organized by Federal Electric Corporation (FEC), of Paramus, N.J., to operate and supply the Line. FEC was a subsidiary of conglomerate ITT. FSI was newly established in Colorado Springs, CO. A respected logistics expert, Gray was FEC point man for Department of Defense contracts worldwide. He won business in Saudi Arabia, Antarctica and myriad other places during a long career.

The DEW Line needed recruits. Turnover was high. Most DEW Liners were military retirees, accustomed to working remotely, even preferring it. This made the workforce humongous – older men formed from a military mindset. I would be a guinea pig, Gray explained, showing FSI how well young people without military experience could fit in and tolerate remote living.

I trained that July at the DEW Line Training Center in Streator, IL, graduating in August. Following a brief visit home to pack my things, I left for the Line. In the wee hours of September 17, I boarded a Military Airlift Command (MAC) C-141 ‘Starlifter’ at McGuire Air Force Base in New Jersey. My destination was the large, military/civilian air base and port of Sondrestrom (Sonde) at the eastern end of a west coast fjord in Greenland.

I stuffed waxed cotton in my ears and fell asleep. I awoke to Training Center classmate Sam Drysdale pounding my arm. An airbag floated in my face. Wide-eyed passengers grabbed for theirs. A cockpit windshield had failed at cruising altitude. In seconds, the giant plane fell tens of thousands of feet as desperate pilots sought air pressure to keep us alive. We limped low into Goose Bay, Labrador, home of the closest runway long enough for a plane so large. Hours later, another Starlifter delivered a replacement windshield and ferried us back to McGuire. We reached Greenland later that same long day.

I enjoyed a normal night’s sleep on a cot at Sonde’s Arctic Hotel, a fancifully named, 2-story concrete barracks. The next morning, on August 18, FSI staffers Dick Corkery and Kevin Madison processed me as a new employee. I met FSI Sector Manager Svend Langsem and his secretary. In coming days, I enjoyed much of what Sonde could offer, a lot given its military antecedents. The gymnasium was well equipped, the bar well stocked. Plentiful food was tasty. I liked it.

On September 23, Sector Supervisor of Communications & Equipment (SC&E) Tom O’Connor issued my orders. At 9:15 the next morning, I boarded a ‘mule of the north’ deHavilland Twin Otter to my first assignment. DYE3 sat 9,000 feet above sea level, north of the Arctic Circle and in the middle of Greenland’s vast ice cap.

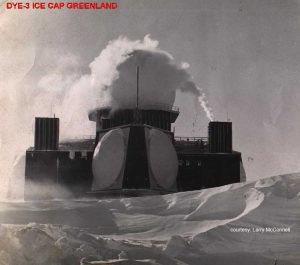

I’ll never forget the first time I saw DYE3, a tiny speck in a vast whiteness. As we neared, the speck became a three-story metal box topped by a geodesic dome. Large convex pods – tropospheric scatter radio antennae – protruded from east & west flanks. We landed on skiis and taxied to an idling Trackmaster, which I entered with my stuff. The building we approached was big, the contrasts shocking. Nothing had prepared me for this. The conditions were fascinating and more than a little frightening.

The DEW Line was organized into Sectors. Well-staffed Main Stations serviced numerous, minimally staffed auxiliary (Aux) sites. Greenland’s DEW line was the DYE Sector, named for our Main Station at Cape Dyer, at the eastern edge of Canada’s high arctic. The DYE Sector had four aux sites. DYE1 sat on a mountain along Greenland’s east coast, a short helicopter ride from Sonde. DYE sites two and three straddled the Arctic Circle (one above & one below) atop the icecap. DYE4 rested on a thousand-foot cliff above the North Atlantic, on Kulusuk Island, off Greenland’s dramatic east coast.

The primary radar antenna at each station could see 200 nautical miles of airspace in 360 lateral degrees. Some 150 miles separated each station from its neighbor. The overlap helped ensure good coverage of the Distant Early Warning Identification Zone (DEWIZ), where we looked for Soviet bombers called ‘Russian Bears’.

DEW Line Aux sites were military outposts operated entirely by civilians. At an Aux site, the ‘Station Chief’ supervised a complement of 12-15 people and their activities. A ‘Lead Radician’ (Lead Rad) usually was second in command, supervising & scheduling the work of up to four radicians and three console operators, guys like me. Radicians were highly skilled, well-paid technicians, able to install, rebuild, and calibrate radar and communications gear. Other personnel included a chef, a janitor, two engine room mechanics and an outside mechanic. Because each site operated 24 hours a day, seven days a week, only about a third of us were awake and working at any given time.

I reached DYE3 at 12:05 PM, in time for lunch. Station Chief Jim Taylor and his Lead Rad, whose name I forget, met me at the top of the 30-foot aluminum stairway leading up from the ice to the front door. I remember Taylor as short, fat and a Southern bully. His #1 was tall, skinny and edgy. I didn’t like either man from the outset. At lunch, I met genial Danish cook Paul Damgaard, who would prove to be a wizard with pizza.

Fred Teeter at the entrance to the Communications Equipment Room where the Radicians lived. The door to the Console Room is on the left. Photo courtesy Fred Teeter Jr.

The next day, from 7 AM to 3 PM, I sat my first watch with Console Operator Paul Tomaszewski. On September 26, from 3 PM to 11 AM, I sat console with Miss America fanatic Rick (last name forgotten). I finally sat solo from 11 PM to 7 AM on October 1.

Like most DEW Line sites, DYE3 was staffed with folks pleasant and not. As a new guy and the youngest, I got an earful from almost everyone. Isolated folks complain when they talk at all. If Heaven were an iceberg, the mood there would be dismal.

And so we come to labor relations. Work rule changes introduced when ITT took the OMS contract from RCA didn’t help the mood. Neither did the issue of union representation, which Greenland workers lacked. The International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) represented DEW Liners in Canada and Alaska, but lacked standing in Greenland. DYE Sector workers had marginally different pay rates, job descriptions and work rules. This wasn’t a new predicament. A union had represented workers and delivered different working conditions in Alaska and Canada for years. My DYE Sector colleagues were offended by their different status. But for the most part, job classifications and staffing were similar across the Line. Pay scale differences from Sector to Sector were minimal.

ITT won the DEW Line by quoting labor costs based on ‘minimum manning’, a clean-sheet look at what each site required to fulfill its mission. The new Console Operator (CO) position was a minimum manning innovation. Before CO’s arrived, every aux site employed five radicians. When not working on equipment, radicians sat at the console watching for Soviet bombers. My uncle considered this a waste of resources. “Why,” he may have asked, “can’t we staff the console with modestly paid people who don’t need technical training?” The Air Force liked the idea.

The console job was simple – watch, report and record. We responded to and recorded everything meaningful that happened at the Station. Did someone call the console to learn the outside temperature? We recorded when the call arrived, what each of us said, and when the call ended. We read weather gauges regularly and recorded the readings. When a flight crossed our airspace, we recorded the path and reported it to Air Force authorities via teletype.