Saga’s, Tales, & Lies.

Unlike the Memories section, War Stories are subjective, often amusing, sometimes larger than life, or just plain interesting anecdotes that DEWLiners would share with one another, if they could, over a beer (or two) on a Saturday night at the bar.

Be sure to visit the Memories section for a series of objective essays containing facts and information pertaining to the DEWLine itself, its history, places, equipment, living conditions, and personal experiences that speak to life on the Line.

CONTENTS

- DEWLine Ingenuity By Lynden T. (Bucky) Harris

- An Honest Employee By Linda Chartier

- Memories of CAM-4 1957 By Doug Consul

- The POW Main Totem Pole By Clive Beckmann

- The Grave at POW-1 By Jack Presnell

- The “First” DYE-3 Site By Bob Davis

- The Flim Flam Caper By Murray Rosen

- Even Eskimos Get Cold By Murray Rosen

- The Prayer Meeting By Murray Rosen

- A Peace Story By Murray Rosen

- The Skin Flick By Ralph Howell

- Smitty and Bennie By Clive Beckmann

- Antique Days at Lizburne By Edward Whitaker

- MAYDAY at FOX Main (Hall Beach) By Paul Kelley

- The Hunting Accident By Paul Kelley

- The Missing Libation By Lynden T. (Bucky) Harris

- The Giggler By Paul Kelley

- The Arctic Star By Clive Beckmann

- A Night To Remember (or – DEWLiners Really Could Be Creative When Necessary By Clive Beckmann

- On The Horns Of A Dilemma (or- Lost at Sea) By Lynden T. (Bucky) Harris

- First Trip North By Paul Kelley

- How Many Souls On Board? By Paul Kelley

- The Arctic Sealer – Fun in the Arctic By Roger Collinson

- A Day To Forget By Dale Brown

- The Spectacle of the Missing Spectacles By Clive Beckmann

- A Failed Polar Bear Hunt By Lynden T. (Bucky) Harris

- Muskeg Mel By Sandi Evans

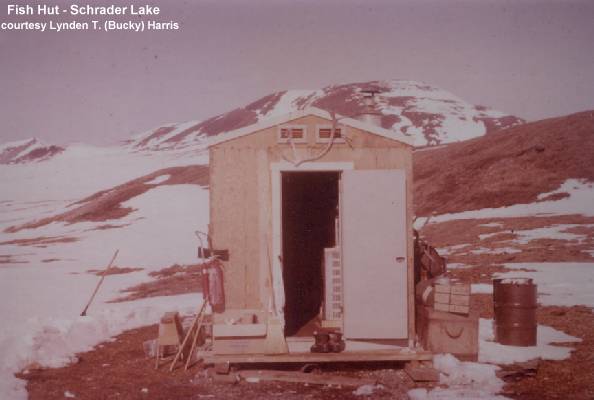

- A Fishing Trip By Lynden T. (Bucky) Harris

- TO: WAR STORIES – VOLUME 2

DEWLINE INGENUITY

By Lynden T. (Bucky) Harris

In the early days of the DEWLine each sector supervisor was required to visit each site in his respective sector on a quarterly basis. As logistics Sector Supervisor in the BAR-Sector, I had scheduled a visit to BAR-C along with Chaplain Paul Maurer. The Chaplain too had this responsibility and I always tried to travel with the Chaplain – thinking that Our Man Above would be watching out for him and I would then be holding his hand….

This visit occurred on a beautiful spring/summer day and our flight to BAR-C (pilot – Frank Gregory) was without incident. Normally, when you land on the runway, station personnel and a vehicle would be there to meet you – not especially anxious to see you, but wanting to get the mail, fresh fruit, produce and of course the movies. We landed at the BAR-C strip, got out of the plane, unloaded the cargo, mail and movies, and after 5 minutes or so no one came to pick us up. Eventually, we told Frank, the pilot, to go on back and that we would carry what we could and walk to the site.

When we walked into the module, the doppler radar alarm was on. I cancelled the alarm and we went through the rooms in the building looking for some site personnel – but to no avail. We joked that apparently some UFO and crew from outer space must have came in and took the men away.

We then proceeded to go to the station garage – about 100 yards from the site proper. There we found the entire site crew sitting on the garage floor making moonshine. The chef had taken dried raisins, prunes, and peaches, the necessary sugar and yeast and had made a mash that had been fermenting for at least a couple of weeks. The concoction looked rotten to me. The mechanic had constructed a cute little still made out of copper left over from construction. They were using the site welding equipment to boil the mash and had large chunks of ice wrapped around the copper tubing to condense the steam. Needless to say that in short order we had about a quart of 180 proof alcohol. The chef took some sugar and burn it in a pan on the stove to add to the moonshine. The color ten resembled a good southern bourbon. We mixed this moonshine with some grape juice and each had a big “belt” (or, two) before dinner. This was not abuse – merely good old country boys taking advantage of their ingenuity. I wonder if Chuck Munshaw and the rest of the crew from that day can still laugh about this incident.

An Honest Employee

A copy of a letter received by Linda Chartier, DEWLine Airforce Contracting Officer

August 16, 1992.

To Whom It May Concern:

Please find enclosed twenty Canadian dollars. This is payment for a few items I have taken from a closing site on.the Dew line.

I am aware that disposed items, that is to say garbage, are not for the taking. Rather than take the items in question I am purchasing the items at a price that I feel is more than adequate.

Sincerely yours

An Honest Employee

Memories of CAM-4 1957

by Doug Consul

One day we heard that a Globe Master aircraft was a about to parachute some construction equipment into the site, so we all gather to watch, the aircraft had flown up from near Boston and circled the site a couple of times, got lined and out came something with four chutes attached, then one chute collapsed and the heavy construction wagon went screeching toward earth, and disappeared through 20 feet of ice, I would guess it is still there.

The site was on top of a mountain and the wind seemed never to stop blowing, on one occasion we were stranded for at least 6 weeks without air support. The picture below shows the first aircraft to make it to our site following the big storm.

We had a young fellow who had the job of filling the Coleman stoves with fuel during the night, the wind blew so strong during many of the nights that he was afraid to go outside to do his job, the result was we often woke up to -40 inside the tents. Many of the tents had to be dug out of the snow each morning as shown in the picture below.

The POW Main Totem Pole:

By Clive Beckmann

In 1972, while I was working at Pow Main, I had the pleasure of becoming friends with 1st Lt. Mike Gallagher, who was a USAF officer assigned to the site. Mike was always doing something unusual to pass the time. For example, he ran ads in the New Yorker magazine, selling pebbles from the beach of the point just north of the site. People were actually sending money for pebbles from the “farthest north beach in the USA”, as Mike phrased it. Then he began complaining about the lack of trees in the area! One thing led to another and he had soon commandeered a telephone pole and a stack of plywood sheets. He cut each sheet diagonally in the familiar “Christmas tree” sillouette, then affixed them to the pole so it resembled a real tree. The plywood was painted green, and the pole, brown. Lastly, he erected a sign at the base of the tree that read, “Point Barrow National Forest”. It became the first “tourist stop” when the tour busses began including the site as a stop on their runs. The “tree” eventually became unstable and was removed as a safety measure, probably in ’75 or ’76.

After the tree, Mike still looked for outlets for his energy, and came up with the totem pole idea. After all, the SE native Alaskans had them, so why shouldn’t Pow Main have one too? He again secured a telephone pole and created all the faces, etc., that you see. The pole was erected (in late ’72 or early ’73) and was another big hit with the tourists. There must have been tens of thousands of snapshots taken of that totem pole over the years! But wait!… the story doesn’t end there.

In ’78, Mike Gallagher was long gone, but the totem pole was still there, being enjoyed by the tourists. Also, there was a Dewline project to replace the Wilcox/Crittenden marine heads (original Dewline equipment) with regular flush toilets or electric Incinolet heads. The station supervisor at the time was George Machuga. He wasn’t all that excited about getting a flush toilet after years of using the marine head. He would sit at the bar, nursing his beer, and confide to his friends that he hated to see the marine heads summarily thrown in the dump after twenty years of faithful service. “Many talented Dewliner butts have graced that head,” he used to say. “It’s a shame to see them go.” Three of his friends, Bob Flanagan (sector plumber), Charlie Mister (sector rigger) and Lloyd Gandy (sector mechanic), took note of his laments and took matters into their own hands. Bob saved the marine head after he ripped it out, then late one night, the three of them went out, dropped the totem pole and installed the head as the “top head” on the pole. They re-erected the pole, then sat back and waited, chuckling amongst themselves and wondering who would be the first to notice the addition. It was several days before the change was detected, then everyone on the site was out there, gazing at the spectical and wondering how it had happened. The three conspirators, of course, kept mum about the whole thing and it was a long time before the whole story came out. Machuga was really tickled that the head had found a new home and was quite proud of the totem. Here’s a footnote to the story: When Machuga was complaining about the upgrade to flush toilets, he often stated, “Yeah, the next thing you know they’ll order all the toilets to be changed to pink!” Well the three conspirators did something about that, too. They managed to locate a pink toilet somewhere at the NARL camp or in the village, and they installed it in the bathroom where Machuga always did his business! (If you ever get back to Pow Main, look in the bathrooms in the north train… it’s probably still there). What hilarity, hearing Machuga’s comments after seeing the toilet for the first time.

Bob Flanagan is alive and well, living in Fairbanks. He has a wealth of Dewline war stories to tell. Charlie Mister, Lloyd Gandy and George Machuga have all gone to that big Dewline in the sky, bless their hearts. As for Mike Gallagher, during the Desert Storm conflict, I turned on my TV one day and who was giving the daily briefing but… Lt Col Mike Gallagher!! That was the last I saw of Mike, 1992. It’s quite possible he’s still in the military, although he’d be approaching 30 years of service. For all I know, it may now be General Mike Gallagher!!! I’d like to find out. If you have any way to inquire, please let me know the results.

Clive Beckmann

The Grave at POW-1:

By Jack Presnell

During the construction of the Dewline, a skeleton was found on the site and was reburied with gravel that was hauled from the beach. The construction workers built a fence around the site. I had always heard that it was a child’s skeleton that was buried there. During the early days on the Dewline you would occasionally find a skeleton lying in an open hole out on the tundra, or a wooden cross sticking in the ground to mark a burial site. There had been Eskimos scattered all across the arctic back before World War Two. When the trading ships failed to come up during the war-I was told by some of the older Natives-the people starved out in Alaska and had to go into Canada, where they could get food from the Hudson Bay Co.

I read once that Charlie Brower lost a herd of reindeer at Pitt Point, back before the Dewline was built, so it’s possible that it could have been some of that family.

Back to top of page

The “First” DYE-3 Site:

By Bob Davis

In may early 1950’s we arrived via Flying Tiger Airlines at Sondrestrom AFB in Greenland. After unloading our equipment, the Tigers did a fine job of showing the air force how to fly. They used only half the runway and when they were parallel to the control tower they stood the Super Connie on its tail and were airborne at (guess) a thirty degree angle. Anyway Dye 2 and Dye 3 did not have the luxury of GPS in them days so we had the director and asst director of the Hayden planetarium as our position locators. I was at Dye 3 and after being taken out to take sun shots the asst director at our site determined where we should be. We loaded our equipment on the C123 plane that took us and our equipment to the site and we proceeded to set up our three Jamesway shelters, a diesel shack and dig our outhouse hole and garbage dump hole. After about a week with further positioning sun shots it was determined that we were not at the correct location so we had to break camp, repack everything and the sir force sent the C123 back out so we could move to the site that was set out for the feasibility communication study. I was the prime contractor rep, the assistant director of the planetarium, seven Page communication people who were sub contractors, one air force survival expert and one Doctor lived there until Sept. Our best day was in July when a bird, 175 miles off course showed up and rested overnight on our antenna. The site sat on 11000 feet of ice. 9000 feet of it above sea level and 2000 feet of it below sea level. Incidentally every one was great except the Doctor who was supposed to be sort of a mind easer in case we got injured. It turned out that he couldn’t stand the isolation and had to leave early.

The Film Flam Caper:

By Murray Rosen

In 1976 after we lost White Alice, I was sent to Pow Main to relieve John McComsky as Station Chief while he was on Vacation. I was met by “Mike” Feda, later Mike Feda-Beckmann. I did not know her at the time. We spoke briefly, and the following morning she left Barrow to begin her vacation. Three years later she was a Supply Spec. at Bar Main where I was Logs. Manager. Since I was the only one who used the site darkroom, Mike asked if I would develope a roll of film for her.

After I printed the first frame, I called Mike and asked that she join me in the darkroom. I asked her where she had gotten that roll of film. She had found it on a Wein/Alaska airplane in 1976. We determined it was that flight she took for vacation when we first met.

The print I made was of a woman and a young boy at the beach. I asked if she knew who they were. She did not. I replied, “Well that is my wife Sophie, and the boy is my son Gary” I had lost the roll of film on my first flight up to the line. Of all the people that Mike ran into during the following three years, what were the odds against her asking me to develop that film ?

Even Eskimos Get Cold:

By Murray Rosen

It was a dark and stormy night at Pow Main during the winter of 1985. We found an Eskimo gentleman trying to get into the train. I went out to talk with him. He was an older man, obviously intoxicated and spoke little English. It took several minutes to understand his friend was missing on a snow machine. He was quite disturbed. I called out the Emergency Action Team.

Bill, the Vehicle Mechanic, and I, jumped into the trackmaster and headed out over the snow covered tundra. We dispatched a vehicle with several men, down the road towards the airstrip. We would try to meet up later. I also alerted the clinic in Barrow.

After about a half hour, through the blowing snow, our lights picked up a snow machine on its side with an Eskimo sound asleep next to it.

We could not arouse him, and although he was alive, he was cold, stiff, and hard as a board. I remember touching his thigh and thinking how hard it was. The two of us struggled mightily to haul the 200 pound man aboard. We sent a message to the Barrow clinic to have a vehicle meet us at the airstrip. He was still unconscious when we transferred him to their ambulance.

A few days later, the clinic reported he was fully recovered and had been sent home. Our training had paid off. The mission was letter perfect, or so I thought. The Contract Monitors thought it was only a “satisfactory” deployment of the team. I always wondered what it would take to get an “excellent” rating. I filed a formal protest but never heard from anybody.

The Prayer Meeting:

By Murray Rosen

During the late seventies, prior to our installing closed circuit television in every room, at Bar Main, entertainment was a priority. Two movies a week were hardly sufficient.

Almost every evening after supper, and certainly Saturday night, Gil Hyatt, admin. clerk to Dennis Kurpius, Bar Sector Manager, would announce over the PA system, “There will be a prayer meeting in B train beginning at 1900 hours” Gil was known as the Reverand Hyatt and the prayer meeting was our euphemism for the nightly low stakes poker game. We used a professional poker table and each man had a monogrammed ash tray and coffee mug, liquor not being allowed in the poker room.

On Saturday night, Ralph Williams, our baker, would bring in fresh hot doughnuts. What a treat they were. We always thought that poker room was the healthiest place on site. No drinking, no arguments, just good comradship at the top of the world. We loved it and life was not bad at all.

A Peace Story:

By Murray Rosen

Those of us who were fortunate to live part of our lives on an Early Warning System station or on any of it’s associated projects, knows this: It’s possible we kept the “Cold War”, cold. For our nations and perhaps the world.

What was it that we found so attractive about life on these cold, remote outposts ? Sure we earned decent livings and the food was good, but was there something more ?

For me, there was a great sense of belonging, a common purpose that bound our lives together and not only enabled us to tolerate but to like each other. Because of the time we spent together, we came to realize we were one family, brothers and sisters working and living together, and liking it.

If that sounds a bit corny, let me explain. Carl Sagan said in his book, “Billions and Billions”, that geometric progression was one of the most powerful ideas in the universe. We all know the story about placing a grain of rice on the first square of a chess board and doubling it each progressive square. When the board is covered with rice, the number of individual grains would be higher than all the rice available in the world. Per Sagan, I once counted my ancestors. My two parents and their parents and so on. Figuring 25 years for each generation, when I got back only to the 10th century, my ancestors numbered 1,099,511,627,776. That’s one trillion. If we all are unconnected individuals, and each of us has that number of ancestors, how does that compute. There have not been that many people born since the dawn of man.

Well it doesn’t compute directly. So what is the answer ?

The answer my truly dear friends, is that we all share the same ancestors. Perhaps every person alive today is related. We were just lucky enough to get to know each other well, and the normal family feelings made themselves apparent. I don’t mean everybody liked everybody. I have a sister I don’t much care for and an ex wife who…….but that’s another story.

I for one will never forget any of you. I will cherish having known you all, until the end of my life.

May 2001, Las Vegas

The “Skin Flick”:

By Ralph Howell

Back when the three 16mm films per week was the entertainment on the DEW Line, I was passing through Cam-M enroute to Cam-3. One evening there was an announcement over the PA. “There will be a skin flick in the station theatre at 7:30”. Because the theatre could only accommodate approx 40 people on a site of approx 100 personnel, the seats were filled long before 7:30.

At 7:30 sharp we were surprised by the entrance of an elderly RC priest. who proceeded to the projector and started it up. The lights dimmed and the screen displayed…. “The Curing of Seal Skins by Hudson Bay”. It was a long evening as we were all too embarrassed to leave before the end.

Smitty and Bennie

By Clive Beckmann

We had two pilots flying the ol’ DC-3 (N21769) in the ’60s. They were Smitty and Bennie (both now deceased, bless their souls!). They were both known for their partying stamina when RONing at a site. In fact, when preparing to depart with them on an early morning flight, you’d be on the verge of chickening out as you glimpsed their bloodshot eyes and haggard, unshaven appearance. But they’d commandeer a coupla quarts of tomato juice, crawl on board 769, and away we’d go! (I never did hear of an actual case of chickening out by any Dewliner, although many threatened it.) At any rate, I was with them on an early morning flight one day and they were both in hurtsville as usual. Bennie got up to use the head and a few moments after he closed the door behind him, Smitty figured he had it all hangin’ out over the commode. Always the jokester, Smitty figured he’d run Bennie a little interference. He reefed back on the yoke and pulled what seemed to me to be 3 or 4 G’s. Unfortunately, I was in the process of changing seats when the maneuver commenced. It literally drove me to my knees! Smitty glanced back thru the cabin and saw me and really felt sheepish. He motioned for me to come up front, then offered to let me sit in the mechanic’s jump seat by way of apology. I had to get up a few moments later to let Bennie thru when he returned from the head, the front of his britches showing great dark splatters of pee. But he said nothing accusatory to Smitty… his only comment was, “Lotsa CAT this morning!”, as he slid into the right seat. This was evidentally how the game was played. You couldn’t acknowledge a practical joke.

So there we were, flying along straight and level again, and I was beginning to re-enjoy the flight when the aircraft began pitching, yawing and rolling, and I saw Smitty firewall one of the throttles. The both of them craned their necks to look out of the right side window, then they invited me to look. The prop was feathered and stationary!!! “It’s stopped!!”, Smitty cried out into my ear. “Yeah, I couldn’t help but notice”, I replied. “Whatcha planning on doing now?” Smitty kinda shrugged his shoulders and said, “Guess we’ll try to restart it!” Hooray, three cheers for the good guys. I was glad we were all on the same team. Anyway, that flight was completed uneventfully, since these sort of events were apparently considered to be normal occurrences!

Clive B.

Antique Days at Lizburne:

By Edward Whitaker

After a quick scan of those listed at the various sites, I feel more than antique.

In June, 51, I went ashore at Lizburne with 28 enlisted troops, two officers and a dog that had been purloined as we came through Nome. I was the first (and only) radio op on the site until August, 51 when I came home on emergency leave.

All of the troops with the exception of a medic from Spokane, were Oregonians, having been activated with the 142d AC&W Squadron May 1st.

Gaasland Construction had been on site for two summers, and their work was less than satisfactory. They wound up hiring GI drivers, using GI vehicles and GI gas as their main motor pool.

We lived in tents and had only been at F-7 24 hours when the hard work began…unloading a ship laden with all the C&E gear, rations, vehicles, fuel and God only knows what else.

Our rations were primarily 5-in-1, supplemented with a freshly killed caribou from time to time.

My radio equipment seemed like early Marconi, but in truth was just obsolete WWII gear. Setting up the transmitter at sea level meant most of the RF went straight into the cape, but from time to time we were able to reach Ladd AFB…most traffic went through Nome.

Lots of “war stories from those pioneering days” I’d be pleased to share with anyone interested.

Edd Whitaker

Speedway Video Productions

Portland, OR

Mayday At FOX Main (Hall Beach)

By Paul Kelley

Northern NORAD conducted periodic inspections of the Canadian sectors of the DEWline. What their precise terms of reference were I do not know but, to conduct their inspections, they required air transport which was provided by the RCAF Air Transport Command. My earlier encounter with the team and their aircraft (a North Star, tail number 17520), as noted in a previous story (“A Busy Day at Hall Beach ‘International’ Airport,” WAR STORIES – VOLUME 3), was not near as eventful as this one.

I was on day shift (0700-1500) again this week but not on the console when 17520 arrived on Thursday, 1 Feb 1962. If I had been it would have been just that bit different than the arrival of the first inspection team – at least in terms of local air traffic. The sun was just in the process of returning after the dark period for, at most, 2-3 hours per day. There was no Sealift or Airlift in progress and the only aircraft movement was the occasional lateral flight by CF-IQD. In short, very quiet indeed. Being on day shift and in the equipment modules I didn’t see any evidence of the Inspection Team although I knew they were around and about.

Friday, 2 Feb, dawned – if one could call it that – rather gloomy with a low overcast. Overnight the temperature had dipped to -40F or below – a cold one even by local standards. I was on the console when, circa 1030, I received the following on 122.2mc:

“Hall Beach radio this is North Star 17520.”

“Roger 17520, this is Hall Beach, go ahead.”

“Roger Hall Beach, 17520 is ready to taxi for run up and take-off on runway 36. We’re outbound for Cape Dyer non-stop, estimated flight time 2 hrs 40 min, 21 souls on board.”

(Note – the prevailing wind at Hall Beach was to the W-WNW and hence the use of runway 36 magnetic (300 true). For 17520 this would require a 180 turn after takeoff to head E to Cape Dyer.)

“Roger 17520” – and I then repeated all of the above in confirmation, gave him the wind and altimeter and requested he advise again on takeoff.

“Roger Hall Beach, will do, 17520.”

I then sat back and relaxed as there was no other traffic at the time. A few minutes later:

“Hall Beach, 17520, we’re off at 52 past the hour.”

“Roger Sir, off at 52, have a good trip, Hall Beach.”

Once again I sat back for what looked like an uneventful shift. About 2 min later the following came in on 122.2 mc:

“Hall Beach Radio this is 17520.”

“Roger sir this is Hall Beach, go ahead.”

“Roger Hall Beach, we’ve lost oil pressure on number 4 engine (extreme right from pilot’s viewpoint) and will be returning to base as soon as we’ve dumped some fuel South of the station on the downwind leg.”

“Roger 17520 message received and understood. Will advise lower camp personnel to be standing by, Hall Beach.”

Click, Click – (A double keying of the transmitter which is a shorthand way of acknowledgement when otherwise engaged.)

Nothing in the training we had had dealt with this sort of situation so I just went on to mental automatic trusting that common sense would prevail.

The first thing I did was relay the message to the Sector Controller in his room behind the screen behind the console. On duty that day was Flt Lt Doug Finch, RCAF. Then I used the telephone to patch into the PA system, Ext 69:

“Attention all personnel in the lower camp. Be advised that RCAF North Star just departed Hall Beach has lost number 4 engine and is returning to base as soon as he has dumped some fuel South of the station. Will the Station Chief please call 21 (the console extension).” And then I said it all again just to be sure.

Joe Esposito, the station chief, rang and I filled him in quickly and rang off.

What was weird was that I wasn’t really thinking at this point – just trying to be as clear and concise as possible in what I knew was a one way communication exercise (vis a vis the lower camp) that had to be right first time. The guys who might be needed in the lower camp had to have the full plot and no more and as quickly as possible. I was completely and utterly calm and alert and very much aware of this. The only thought that crossed my mind was my friend (now at FOX 2) George Guerin’s comment about ‘this only happens in the movies!’

About 2-3 minutes later the following came in:

“Hall Beach this is 17520, number 2 and 3 engines are now siphoning oil. If I can make the turn on final I will be attempting a wheels-up landing North of runway 36. If I can’t I will try and put her down on the shore ice. Oh, I guess this is a Mayday, so —Mayday.”

After his first sentence I recall uttering ‘shit!’ to myself.

When he finished I replied with: “Roger sir, acknowledge your Mayday. Good luck.”

Click, Click.

For an instant I thought of advising him of emergency services being alerted or words to that effect but thought better of it. Hell, I didn’t even know if we had anything that could be of any use in these circumstances and if we did he knew that they would be deployed.

I didn’t bother with the intercom this time but yelled over to the Controller: “We have a Mayday with 17520!”

I immediately jumped on the PA system again as the Controller trotted round to see what the hell was going on.

“Attention all personnel in the lower camp, this is not a drill, repeat this is not a drill. RCAF North Star has declared Mayday. He has now lost number 2 and 3 engines as well as number 4. He will be attempting a wheels-up landing North of runway 36 if he can make the final turn. If not, he will do the same on the shore ice. Activate all emergency procedures. Repeat this is not a drill. Mayday, Mayday.”

I did not repeat it as it was too long and I didn’t want to be babbling if he called in again. They were already on alert anyway, with what I didn’t know and never did find out. I don’t think it was much other than the foam truck and maybe Dr. Roche – if he was on site at the time.

As the Controller heard all this it was not necessary to repeat it. He ran out in the corridor, down to the door at the East end of the equipment modules and outside. He was shouting back to me what was happening. We were both acutely aware of the 4 POL bulk storage tanks 400 yards North of the final approach to runway 36 – well out of the way for a normal approach but this was not normal. With number 4 engine gone and not having any idea how much 2 and 3 were still contributing, it did cross our minds that trying to make a left turn with only number 1 fully operational was going to be tricky and require all the left rudder she was capable of. Time seemed to stop for about 10 minutes while all this took place.

Somehow, 17520 made the final turn, and was coming in North of runway 36. He then disappeared from view and, as we waited for the worst, we both (even me inside) heard a muffled thump – and then nothing else.

The Controller came back in and the two of us waited for some word of what happened. Eventually his boss, the Station Commander, rang to say that the pilot made a beautiful wheels-up landing in about 3′ of snow N of the runway. Bar the propellers, the aircraft did not appear to be damaged and no one was injured bar the co-pilot who had something wrong with the small finger on his right hand. A bloody miracle and compliments to the two guys up front for a job well done.

Once we knew all was well, Flt Lt Finch asked me for the tape of the air-to-ground conversations just in case someone requested it. I crawled under the console, removed the panel and, as I went to remove the tape, discovered that the dreaded Telefunken had had one of its fits, probably sometime earlier. There was scrunched up tape all over the place. The thing wasn’t alarmed and, without checking it regularly, which no one did, there was no way of knowing when it decided to go wonky. This would turn out to be an embarrassment, but a minor one in the overall scheme of things.

About 45 min after the ‘landing’ there was a bit of commotion out in the usually empty hall in the equipment modules. There were people chatting and heading towards the Surveillance Room. The Station Commander, the pilot, a Flt Lt, and one or two others showed up. The pilot was obviously well stressed but, despite this, shook my hand and thanked me – for what I am not sure. Then they requested to be put through on the ‘hot line’ to Northern NORAD.

The ‘hot line’ had just recently been installed. It was a red telephone that sat on the left side of the console and was a direct connection to the SAC operator in Omaha. I got the connection to Northern NORAD for them and then handed the phone to the pilot. I deduced he was speaking with an Air Commodore and, although I don’t know what the latter said, it prompted a bit of a telling off from the pilot. Very refreshing to hear a Flt Lt reaming the AC a new one. My respect for him rose even further. When the call was finished they said thanks again and left – but not before being advised of the Telefunken’s non performance. As I said earlier, embarrassing but nothing more.

And that was that. This was the only Mayday heard in FOX Sector during my time there (Feb 61-May 62) and 17520 was the largest aircraft to encounter difficulties during this period. The only other two were:

CF-CZL (C46) lost its right undercarriage on landing at CAM 4 (Pelly Bay) and crunched to a rather messy halt (subsequently repaired and flown out) and CF-HEI (C-46) did something similar at CAM-F (Scarpa Lake) on 09 Aug 61 (damaged beyond repair). In both cases there were no injuries – just embarrassment.

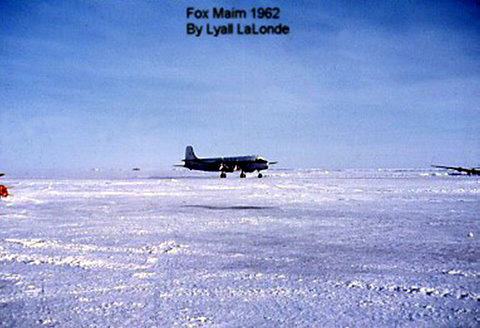

PHOTOS 1 & 2

As I was on day shift during this period it wasn’t until about a week later that I managed to get down to the lower camp to view the scene and take these shots. In photo 1 (below, left) note the few dangly bits hanging off the fuselage below the tail. Apparently this was the only exterior damage to the airframe. The aircraft is sitting just North of the threshold of runway 36 (360 magnetic = 300 true in 1961) and, having skewed to the left before it came to a halt, is aligned to 260 true (approx) and diagonally opposite the hanger located about 200 yards to the South.

(Click to enlarge.)

- Photo 1.

- Photo 2.

In photo 2 (above, right) you can see the remains of the mangled props piled in front of the aircraft. Standing between 1 and 2 engine mounts is Walt Getman of the DOT Met Station who accompanied me on my walkabout. Under the horizontal tail plane, the 4 POL bulk storage tanks can be seen, dimly, at 500 yards distance.

The Merlin engines had already been removed for examination. The outcome of the latter was a new set of guidelines to be followed when aircraft had sat out overnight in very cold weather. Despite Herman Nelson heaters etc., it was decreed that if the temp fell to -40F or below flying would be curtailed until such time as additional checks were made to ensure that the engine oil viscosity was deemed acceptable – or something like that. When 17520 lost number 4 engine it was because the oil was not thin enough to flow properly to where it should. How the subsequent siphoning business occurred on 2 & 3 engines I don’t understand and have never received a satisfactory explanation.

Lyall LaLonde – Mechanic, FOX Main

I never, knowingly, made Lyall’s acquaintance while at FOX Main during Feb 61-May 62 but now I know he was there as well. I became aware of this 50 years later (2011) when ‘chatting’ with him via email re: another subject. It turns out that he was working in the Depot Level Maintenance Shop in the Lower Camp on the day of 17520’s mishap and that, earlier, some of the crew had had their meal with him and others in the Lower Camp Mess Hall.

He first became aware of the situation courtesy of my announcement over the PA system. He too had a camera and took four shots of the aircraft some time before I arrived on the scene – with propellers and engines still in place. Not only that, his photos are in colour – a refreshing change from good old black and white. Following are his photos.

(Click to enlarge.)

- View looking North East (true).

- View looking East (true) with the POL tanks visible in the distance.

- View looking true North.

- TransAir DC-4, CF-IQM, arriving at Hall Beach from Winnipeg. On the right of the photo ia a partial view of 17520’s wing.

17520 in happier times. Courtesy 1000AircraftPhotos.com.

17520 sat where it was for several months. Eventually they brought in a crew to salvage it. First, a D-8 cat was used to level a path the 200 yds or so back to the apron in front of the hangar. Then huge neoprene balloons were inflated under the wings and fuselage to raise the aircraft off the ground. Then they dropped the undercarriage and towed it back to the hangar. There they installed new engines and, after a test flight, flew it south to serve another day.

Postscript

Disposition of the Aircraft.

Accident reports indicated that the aircraft was damaged beyond repair and written off. My memory – possibly flaky as it has been known to let me down from time to time – tells a different story as I recounted in the final paragraph of my text above.

PK Comment:

While I am in no way qualified as an air accident investigator, everything I could see and subsequently heard was that the aircraft, bar the props and engines, was hardly damaged at all. I was on duty when the ‘lift’ of the aircraft was performed so did not see it as such. What I did see was the aircraft when it was back in the hangar – still without engines. On this visit to the hangar is when I spent more than a few minutes inquiring as to how they had accomplished this and learning of the inflatable balloons. The RCAF may well have decided to scrap the aircraft at some later date but my memory tells me that that decision was not made while it was at Hall Beach and that new engines were mounted and 17520 was flown South. I’ll happily stand corrected on this by anyone who can confirm otherwise but, until the….

Paul Kelley

The Hunting Accident

by Paul Kelley

By way of background, two notes. I never had a camera prior to heading North but, before I boarded the DC 4 in Dorval for the trip to Frobisher and Hall Beach in Feb 61, I had a few hours to kill and was inspired to go down to St. Catherine St and buy one. One of my better spur-of-the-moment decisions and, hence, the collection of photos I now have. The second point, unbeknownst to me until I arrived at Hall Beach, was that at least one of the radicians on site had to be competent in the arts of the dark room. This was because the radars had a camera facility attached and someone had to be able to develop and print the output should it be used. In my 15 months it never was used for real, only periodic testing. When I arrived I discovered that the guy that handled the dark room was the guy I was replacing. Nobody else had expressed any interest so, more by default than design, I took over his mantle and received a crash course on how to do everything before he left. So there I was – new camera and a fully equipped dark room and had yet to take a single photo.

Now for the tale.

Some time around mid Sept 61 I had occasion to use the dark room for a special purpose – X-ray development. At the time the regulations in NWT were that only the Inuit were permitted to carry fire arms although we had 6 M1 rifles locked and sealed in the Station Chief’s office. As there was still a minimum accumulation of ice in Foxe Basin a party of Inuit had been out walrus hunting in their boats. One group, from Igloolik, were hunting near Jens Munk Island, E of Igloolik and about 60 miles N of Hall Beach, when one of the women was accidentally shot in the right thigh with a .303 rifle.

No one, of course, knew anything about this until the party showed up at Hall Beach in their boat about 2-3 days later. They only had something like a 5 hp outboard on this 20′ wooden whaling boat and had made very slow progress trying to get S to where they knew there was a doctor. Al White, the Hudson’s Bay agent in Igloolik had been known to remove the odd appendix in an emergency but I guess they thought better of trusting themselves to his ministrations. In any event they appeared, literally out of the blue, carrying this woman. Luckily the doctor was on site at the time. (We had one MD and one Dentist per 500 mile sector and our two medicos arranged their schedule so that one was at Hall Beach and the other at Cape Dyer on Baffin at any time. Then, roughly bi-weekly, they would swap locations stopping off en route at any intervening sites that required their services)

As soon as they got her into the sickbay the Doc quickly ascertained that gangrene was setting in. It was also evident to all concerned that she was 7-8 months pregnant! Great! He cleaned her up, gave her the necessary jabs to counteract the infection and then took several X-rays to determine what he was dealing with. I happened to be up and about at the time and he asked me to set up the dark room to develop them ASAP and I did so. It was interesting as the X-ray negatives were much bigger than anything I had dealt with before but they were just going to be negatives, no printing involved, and it all turned out to be quite straightforward. By this time I was well versed in dark room procedure and was pleased that I could turn them around in about half an hour. I always recall removing the finished negatives from the stop-bath and looking at them under the red light. I was not in any way medically trained but it didn’t take a genius to recognise a shattered femur – little pieces of what was obviously bone scattered everywhere in the thigh. The bullet apparently had exited the leg but the mess it left behind was quite something.

I delivered them to the doctor and was struck by the lady as she lay in the bed. She managed a wan sort of smile as I entered and didn’t seem in the least distressed. She was obviously sedated but seemed to be coping with admirable stoicism. After several days laying wounded in an open boat I guess a comfortable bed was not half bad in comparison.

After a look at the X-rays he determined that he could not possibly operate locally to repair the damage. Then began a series of phone calls South to RCAF Air Transport Command in Ontario to see what arrangements could be made to get her out of there to where she could get proper treatment.

As luck would have it there was a slim chance we could move her that night. The northern most RCAF base was at Resolute. There was a C-130 there at the moment in the process of evacuating the summer personnel prior to the onset of winter. It was the last flight out. We didn’t have direct communications with Resolute at first and were working via Ontario. However we had the RCAF in Ontario tell Resolute to come up on some frequency in the 20m band and Glynn Nolan, our Comm Centre operator (ex RAF and 30 WPM in Morse) cranked up the ham gear (431B1 Collins Multi-band transmitter – 1000W and 51J4 Collins Receiver) and made direct contact with them. We used to chat regularly, via Morse, to Resolute, Sachs Harbour, Mould Bay, Isaachsen and Eureka but never did raise Alert for some reason.

The doctor explained the situation to the pilot of the C-130. Apparently the flight was going to have about 50 passengers and a helicopter on board when returning S. It was the best part of a 2000 mile run to Ontario and he said he would have enough fuel to make one pass at landing at Hall Beach. If that was not successful we would have to make alternative arrangements. But he was more than willing to have a go when he came down that night.

I was on the console when we picked him up inbound from Resolute. The trouble was that the wind had picked up and what little snow had fallen was blowing around furiously. 200′ above the station apparently it was as clear as a bell but, on the runway the visibility was down to 1/2 mile in blowing snow – very much below minimums for normal air operations. When he was about 100 miles out I notified the Station Chief and Military Commander of the situation. They immediately arranged to get every available vehicle on the station with headlights to line up on each side of the approach to the runway and light the thing up like Broadway.

I advised the pilot of the local weather and what was being done to assist. I also advised him that our beacon antenna was 1/2 mile S of the runway. (What I suspect to be the new arrangement makes much better sense) He then flew a standard pattern using the beacon as guidance and allowing for difference between its physical location and that of the runway. This involved homing in on the beacon and, when directly overhead, flying the same course for 2 miles, turning left 120 degrees and flying 2 more miles and then left again 120 degrees and returning 2 more miles when, given a little luck and good lighting, he might see the runway.

I tracked him to within about a mile, talking him in all the while, when ground clutter on my scope, although minimal, rendered it useless close in to the station. It was then his call. Apparently the ‘lighting’ system did the trick as he advised me he could see the glow and touched down on the threshold first time. We didn’t hear it in the equipment modules but were told a big cheer went up when he did. This was the first time that a C-130 had been to HB and he blew everyone’s mind on the runway by quickly coming to a halt and then reversing!! back to the apron in front of the hangar. This had not been seen before and never was by me.

He was on the ground for about 15 minutes while they loaded the lady on board and then he was off to Ontario. Two days later we received word that her leg had been saved and that both she and the baby were recovering well. She gave birth several weeks later and the air crew received a commendation for their efforts.

Paul Kelley

The Missing Libation

By Lynden T. (Bucky) Harris

Back in 1965, I was the Logistics Supervisor for DEW East in Greenland and we were having a DEWLine wide logistics conference at PIN-M. Having access to the Class 6 store on Sondrestrom, and booze at $1.25 per 40 ouncer, I was tasked to bring the booze – two cases of various brands. Flew to DYE M with the booze to spend the night and then to fly on the next day to PIN-M. George Pilipuck (sp) and Pete Whitwicky (both Logs Supervisor) met me at the plane. I took out 1 bottle for us to damage that night and went from lower camp to the site proper to spend the night. Need I tell you that when we were ready to take off the next morning, we had not a drop of booze left – the two cases had disappeared. That was 37 years ago and now I do have senior moments but I will never forget that, nor will the other guys that were at the conference!!!

Bucky Harris

The Giggler

By Paul Kelley

One evening there were about 30 of us around a bunch of tables all pulled together quaffing multiple cans. I was seated next to one of the guys and attempting to practice my french amidst the din. As I tried to get my head around some peculiar irregularity he would turn to me and shout an explanation. As he did this he usually left his beer can on the table. As he explained whatever, I noticed a hand, not his, remove the can from view and replace it. This happened several times and I was wondering when he would notice that the can was becoming empty rather faster than it should. Seated on the other side of him was one of the Inuit guys who loaded the aircraft etc. and, as I understood it, not permitted to sample the delights of Molson’s or whatever. My friend was rather large and I couldn’t see the owner of the hand when we were talking. At last, my friend happened to turn while ‘the hand’ was in action. I could see him tense up while debating with himself how to handle this situation. He was provided with his answer by the owner of the hand breaking out into a very typical Inuit giggle. There was no question of guilt just a question of what to do about it. Both of us broke out laughing. You just can’t get angry at a guy when he is giggling. It’s just not possible. So we giggled too and bought him a beer. Bugger the regulations.

Paul Kelley

The Arctic Star

By Clive Beckmann

The Arctic Star was a C-54 aircraft that was used by USAF and PHQ VIPs to travel to and from the Line on inspection tours. It was based out of Griffith AFB NY. Back in the late ’60s, the Arctic Star was due into Bar Main, the eastern-most Alaska site. I was on Sector duty at the time and just happened to be at Bar Main. I’d heard that Sam Bennie was aboard the Arctic Star and I wanted to get a peek at him, having never met the man. So Al Bonito, Nick Van Valen and myself went down to the site airport to observe the de-planing process. The ol’ Arctic Star made her approach and landing and taxied onto the hangar pad. The staircase was wheeled into position, the passenger door opened, but no one came out. We all stood there waiting for something to happen (all the site and sector big-wigs were also standing in the crowd of welcomers) but not a soul was seen passing thru the passenger door. Then, after what seemed an eternity, here comes Sam Bennie, drunker than a skunk, passing thru the door with a guy on each arm to help him down the staircase! Why they thought they could help him is beyond me because, as it turned out, nearly everyone on board, with the exception of the flight crew, was lit to the gills! I mean, they were really crocked. But Sam, as much as I know how he could well hold his liquor, was just a drink away from oblivion. Yet here he came, stumbling down the staircase with his fractured helpers, a big grin plastered across his mug. They quickly loaded all passengers into the bus and whisked them away to the site. I did not attend the party that was held in the bar that night but I often wondered how many of the VIPs made the scene. My inclination is to guess that many of them, upon being given their room assignments, crashed and burned for the night. But I happen to know of the drinking prowess of Dewliners and if I had to bet, I’d say that after a few hours of coffee and clean up, most of them made their appearance at the bar, red hot and ready to hit it again!!! 🙂

Clive Beckmann

A NIGHT TO REMEMBER

or

Dewliners Really Could Be Creative When Necessary

By Clive Beckmann

The war story known as “A Night to Remember” was an incident involving the bar at Pow One. However, to appreciate the story, one has to be aware of some other facts, which I will now present (plus it’s an excellent excuse to be “windy”).

Back in ’67 I was employed in the Alaska sector of the Dewline as a Sector Radician. My cohorts were Al Bonito, Training Specialist, and Nick Van Valen, Sector Radician. We comprised what had come to be known as the “Sector Training Crew”. Since there was never such an official title, here’s a little background on how it originated.

During the CPET inspection earlier that year, our marks in the area of electronics training had been really dismal. There were two kinds of discrepancies the CPET were dishing out in this area.

The first kind was known as a “personal discrepancy”. Any radician with more than one year of service was expected to have achieved “4-level” qualification in one Category 1, and two Category 2 C&E equipment groups. If this requirement was not met, a personal discrepancy existed.

The second kind of discrepancy was known as a “station discrepancy”. It was expected that on any given site, each equipment group was covered by at least two radicians who held a “4-level” or higher in that equipment group. If there were not at least two, a discrepancy existed.

When the CPET team departed Alaska sector that year, they left behind a total of 70 C&E training discrepancies. Being as there were seven Dewline sites in Alaska at the time, that was an average of ten training discrepancies per site! I don’t remember whether or not the government issued a “cure” notice or not. What I do remember is that management, from the site level, through the sector level and on up to the PHQ level in Paramus, was in an uproar. How did the sector C&E training status come to be in such a deplorable state? I believe I remember some of the causes.

Cause #1: For over a year there had been no sector radicians or Training Specialist in the Alaska sector. Of course, the sector rads provided much of the training and level testing that normally occurred in the sector. At the time, the premium pay rate for a Sector Radician was only 25 cents an hour. It was a known fact that sector management was trying to promote site radicians into the three available sector slots but there were no takers. The main reason was that there were very few site radicians who met the qualifications for sector radician. An alternate reason was that there were not many guys who were willing to put up with living out of a suitcase for 12 months out of the year in exchange for the paltry premium pay rate. The 25 cents an hour (about $600 per year) was perceived as a pittance for losing the luxury of having your own room at a site. Anyone who had the gumption to invest the time and energy to achieve advanced training levels in the C&E equipment would be much better served to hold out for a promotion to Lead Radician, which offered 50 cents an hour premium pay.

Cause #2: During the previous year there had been plenty of resignations in the sector. The economy in the lower-48 was such that there were a lot of desirable jobs available for electronic technicians, and more guys were leaving than were being hired. The manning level had gotten to a critical point and many sites had only four radicians on board. In ’67 there were usually six or seven rads per site. One of the effects of this low manning figure was that with only four rads assigned, there was little time left over for the lead radician to accomplish local training of his work force. When a site went down to only four rads, they all worked seven 12-hour days per week (84 hours). That translated into 112 straight time hours of pay per week. That was around $600/week, big bucks for 1966! This was another reason no one wanted to become a sector rad. As soon as you were promoted you were automatically limited to working 54 hours a week, which meant you were paid 61 straight time hours. Under these conditions, a sector rad working with a site rad for training would be earning just a bit more than half the wages of the site rad. No wonder no one wanted the promotions. The same situation made the sector Training Specialist slot impossible to fill. Although the hourly rate for this slot was a couple bucks per hour higher than the rad slot, it was still substantially less that that of a rad working a 4-man shift because the Training Spec was also limited to putting in only 54 hours per week and he did not get premium pay for hours in excess of 40 in a week.

So the sector training situation was in a bad way and management had to come up with a way to immediately start showing an improvement in the training status. They did it by coming up with a bribe. They offered to guarantee a transfer from Alaska to Greenland to any rad who agreed to go into the Training Spec or the sector rad slots and remain there for at least one year. This was a great deal because the Greenland slots offered a big boost in income due to the fact that the work week had a lot more hours than Alaska and the income was all tax-free. Al Bonito was offered the Training Spec slot and Nick and I were offered sector rad slots. We all accepted.

The Alaska SSC&E at the time was Dave Mason, an Englishman. He was quite happy to have the three of us to clear his 70 training discrepancies. He had been given a mandate to have the training status brought to an acceptable condition prior to the next CPET visit, which was just over a year down the road. Because of the mandate, Dave spoke for the Sector Superintendent when arranging our travel schedules. He and Al wished the three of us to travel as a team, which a lot of the time would negatively impact the passenger loading on the lateral aircraft, and also the room availability at the sites we were going to visit. But negative impact notwithstanding, Dave’s desires were not to be disregarded. He was imbued with the power to do as he pleased. Because we were going to be traveling together, and because our primary mission was to accomplish C&E training, we became known as the “Sector Training Crew”.

After several months of operation, the Sector Training Crew had already created quite a reputation for itself. We had come to be known as hard-working, hard-partying dudes. When we hit a site, Al would lay out a schedule for us all that would maximize the amount of training and, consequently, the number of 4-level evaluations we could administer during our typical 3-week stint at a site. The hours were long but when we got off duty we headed straight to the bar for some much-needed relaxation. To boot, we had a big travel trunk that supposedly served to carry all out training paraphernalia from site to site. But it was rarely filled with training aids. It’s primary purpose was to haul a big supply of Mexican food.

In ’67, the Dewline menu was strictly meat and potatoes. There were seldom any ethnic items featured, much to the chagrin of site personnel. When the Sector Training Crew arrived at a site, the remainder of the day was dedicated to interfacing with the Station Chief and the Lead Radician in order to hammer out our schedule. The evening was designated as the Sector Party Night. We would begin by forming up in the bar after the evening meal. Everyone would wet their whistles by way of getting primed up for the festivities to come. Before long, Al and I would set up our electric guitars and microphone and begin a jam-fest which would usually last into the wee hours of the morning. The booze flowed and everyone got with the program. Nearly everyone had a streak of “ham” in them and would take their turns at the microphone, singing their favorite songs with Al and I providing the musical backup. Then, along about nine or ten o’clock, when everyone was starting to get hungry, we would take a break and head for the kitchen. We would use the big baking trays that were provided in every kitchen, and load them up with stacks of homemade tostados and tacos. Everyone loved it! After stuffing ourselves, it was time for more beer and music. This activity continued until everyone was ready to hit the rack. As was usually the case, we were all hung over the next day but the feeling was, “Hey, we’re tough! We work hard and we play hard!” There was seldom a person on the site who didn’t jump feet-first into the first night’s festivities.

Okay, so much for the “background” info. Now, on to the war story. We had just arrived at Pow One on the last flight prior to the Thanksgiving Holiday. This trip was like a homecoming for Al. He had been the Lead Rad there prior to accepting the Training Spec promotion, and this was his first return trip. The Station Chief was W.C. Smith, a retired Navy Chief who had a liking for Cutty Sark. The whole Pow One staff was made up of partiers. However, within minutes of our arrival at the site, we became privy to some terrible news. The site was virtually zero-balance on alcoholic beverages! We took a quick inventory and came up with half a bottle each of Creme de Menthe and Kahlua! This was a dual tragedy. Not only would we have to forego our traditional Sector arrival party, but the entire Holiday weekend would be spent dry! The whole site compliment, and now us sector weenies, felt just terrible about the whole situation.

The reason there was no booze on site was that there had been a lot of recent requirements to move official Dewline freight. Consequently, Pow One’s booze order, which had actually made it up from Fairbanks to Pow Main, was locked up in the Wien Airlines security cage in Barrow village. So near and yet so far! There were cases of beer and cases of booze and cases of wine a mere 80 miles away, but it may as well have been on the moon for all the good it would do us for the upcoming weekend. After supper we all gathered in the bar to lament our predicament. There we sat, about 15 long-faced Dewliners who all looked like they had just lost a good friend. There would be no other lateral flight until after the holiday, four or five days down the road. Of course, the lateral flight was the only aircraft authorized to land at the Pow One military landing strip. Any other aircraft that wanted to land had to obtain 30 days advance permission from the Air Force contracting office. And, to boot, for permission to be granted, there had to be pressing official business requiring the flight. Suffice it to say, this kind of flight occurred only once in a blue moon.

Well, we all got to talking about the booze shipment sitting just 80 miles away and we were collectively drooling from the chin. To boot, the weather was deteriorating and, even if a plane were possible, it would more than likely be unable to get in to our strip. The more we discussed the hypothetical situation of a chartered freight flight, the more we seemed to believe that it would happen if it were not for the deteriorating weather situation (blowing snow was reducing visibility). We were desperate men! We took to calling the console operator every few minutes, asking for the prevailing visibility. It had continued to decrease until it was only about one-eighth mile in blowing snow. Then, about an hour later, lo and behold, the wind slackened and the visibility came up to about a half mile. We all reacted as though there was a plane sitting on the runway at Pow Main with engine idling, just waiting to spring into the sky, loaded down with the Pow One booze shipment.

Then the visibility began to decrease once again. The collective mood seemed to shatter, with everyone acting as though we had just lost an opportunity to get our shipment. The talk turned to the cost of a charter flight. As I recall, it would run about 500 bucks to charter a Cessna 185 from Barrow. We had at least ten guys present and, to a man, we all declared that we would willingly cough up 50 bucks each if it meant that the shipment could get through. But we all really knew we were just whistling Dixie. Having an unauthorized flight land at the site could easily cost the Station Chief his job and create a major incident with the Air Force contracting office, not to mention calling down the wrath of PHQ on the site.

But wait! That would only happen if word of such an incident were leaked off the site. Hey, what a revelation! We could contract this little caper and just not tell anyone and we’d all get away with it, Scott free!! Right?!! Isn’t it amazing how the mind can play such tricks when under stress? Here, in the space of an hour, we had talked ourselves from an impossible situation, to one that was sure to succeed if we didn’t tell anyone about it. It was amazing, we were all conjuring up “what ifs” about the possibility of a flight that was theoretically impossible. Finally, W.C., who by this point was probably actually tasting Cutty Sark in his mind, got up and left the bar. But he wasn’t heading to his room, he was going in the direction of the station office!

Now we all sat there in silence. What had we done? What if W.C. did something stupid and got fired for his efforts? He was known as a Chief who would bend over backwards to support his troops and it was easy to believe he had left with the notion that he would try to arrange a charter flight. At this point, Al got up and followed after W.C. They were both gone for about a half an hour, during which time we all kept the console operator busy reporting prevailing visibility to us. It was hanging in there at about half a mile. When they returned they were both grinning like the proverbial Cheshire cat.

Yes, they had checked into the possibility of a charter flight. And yes, there was a plane available, old 36Z, a Cessna 182 used by an Eskimo pilot in Barrow to fly freight or passengers to various native villages in the area. And 500 bucks was a viable price! Boy, the room was filled with excitement now!! We all looked at W.C. with anticipation, everyone asking the question at the same time. “Are yuh gonna do it, W.C.?” He just kinda sat there wearing that lopsided smirk he was known for. Then he won the everlasting respect and adoration of each man in the room as he drawled, “Already done it, fellers.”

After the cheers died down to a low rumble, we learned that the pilot was, at that moment, at the Barrow airport, loading up a portion of the Pow One booze order. The Cessna was too small to carry the entire load. The bar literally buzzed with excitement until, about a half hour later, the console operator called to say he was tracking a flight inbound from Barrow. W.C. and a couple of his men headed out to fire up a truck and we could see them driving out to the runway pad. But then the gremlins decided to have a little fun with us. The visibility suddenly decreased to virtually nil, and then seemed to fluctuate to an eighth mile and back. What a bummer! Would the flight arrive, only to circle a few times and then head back to Barrow?

Well, that pilot showed us what Alaskan bush pilots are made of. We could hear the sound of a plane landing but, from the module train, we could see nothing but blowing snow. W.C. later reported that they too heard him land but didn’t see anything until the Cessna taxied out of the blowing snow onto the runway pad. But then a strange thing happened. The plane taxied up to the truck and just sat there. The door remained closed. After several minutes, W.C. decided to check it out and walked over to the plane. What he saw was the pilot, energetically motioning him closer and pointing to the door handle. W.C. popped the latch and the door sprung open, dumping several cases of beer onto the ground. The pilot was surrounded by beer and booze cases! The passenger seat was loaded up, the rear seat was loaded up and the baggage compartment was loaded up. The pilot hadn’t brought just a portion of the booze order. He had brought the whole kit and kaboodle! There were so many boxes packed around him that he couldn’t even open the door by himself. W.C. had to pop it and then unload more of the boxes before the pilot could manage to slide out of the plane.

Well, it was all over in a few minutes. The booze was hauled up to the baggage module, 500 bucks changed hands and 36Z was airborne and heading back to Barrow. We were all ecstatic. The cases were broken open and bottles of booze and beer were transferred to the bar. We were all guzzling, guffawing and clapping W.C. on the back in glee. But our elation didn’t last long. Within 15 minutes of the plane’s departure, the paging system clicked on and who did we hear but the Sector Superintendent, Phil Brady, paging W.C. to call him at Bar Main! We all held our breath while W.C. was gone, wondering if any of us would have jobs in the morning after having cajoled W.C. into doing the foul deed.

How word of our little caper had managed to get over to Bar Main so quickly was never revealed to us conspirators. W.C. said later that Phil began by biting a chunk out of his ass, but then admitted that no one wanted to be dry for the Thanksgiving holiday. It was our impression that because the Sector Training Crew was the lead instigator of the illegal incident, and because neither the Sector Supt or the SSC&E wanted to see us canned, which would create a big problem for them in finding replacements for us, they decided to go easy in dishing out reprimands. Only W.C. and Al were ever chewed on as a result of the flight. I never learned what was said from the company to the Air Force. Did the Air Force know that an illegal flight had occurred? Who at PHQ knew what had happened? There may still be someone around who was privy to what happened at those levels. My curiosity is still pretty intense all these years later.

There was a great time had by all during the remainder of that evening, and for the entire Thanksgiving holiday for that matter. In all my succeeding years on the Line, I never heard of any other such incident occurring. It most definitely was, “A Night to Remember.”

Clive Beckmann

On The Horns Of A Dilemma

(Lost At Sea)

By Lynden T. (Bucky) Harris

This incident occurred in the summer of 1958 or 59. I had been flying east out of BAR M ever week or so to BAR-A, BAR-1, BAR-B, BAR -2 and BAR-C to support those sites logistically,and had been noticing a large cache of POL drums between BAR-M and BAR-1, about 10 miles or so east of BAR-M. I was told that this cache of fuel was placed there by the Navy during WWII and may be salvageable. During the weekend of the 4th of July, I though I would go out and take some samples, send to the POL laboratory, and if the fuel was still good, pick it up and return to BAR-M for use. We were having a cat train go to BAR-1 that coming winter and on the way back, pick up this cache of fuel and save the government a lot of money.

Dave Pennington, Lloyd Foggle and I loaded up the site “emergency rescue boat” – a 14 foot aluminum boat with about a 9 HP motor – lots of food – juices, guns, gas etc, and took off east along the coast line and along the way we got to chasing ducks, seals, etc and having a big time killing a big mess of ducks. We knew we were to stay no more than a couple hundred yards off the coast , using it as a guide and reference point. We got after a flock of ducks and no one was paying any attention to the coast line or the weather. All at once we were in a fog bank so thick you could see no more than about 10 feet from you. No way could we see the shore line or determine which way to go – so we sit put for about an hour and then got to thinking – hell this ocean has a tide and current!!! is it coming in or going out? None of us could tell. Recognize that none of us were navigators. We cranked up and ran about 5 or 10 minutes one way and then we would turn and run 5 or 10 minutes another way and yet we could never get a glimpse of the coast line. The more we ran the more screwed up we were getting but we kept doing this anyway until we ran out of fuel. Then we started to paddle doing the same procedure. All at once we came up beside this big iceberg. I knew we were in deep yogurt then. We were all tired, mad and wanting to fight one another. Each of us was positive we knew the right direction to go. This continued until we had been in this predicament for at least 10 hours. All at once we ran aground. WOW, we grabbed an oar, stuck it in the bottom of the ocean and tied the anchor rope to it and decided to stay there until the fog moved out. After an hour or so the fog lifted – now we had been in the water running and paddling for over 12 hours and would you believe when the flog lifted we found ourselves within 100 yards from the point we had launched the boat at BAR-M a good 12 hours ago!!!

We did retrieve the cache of fuel that winter and brought it to BAR-M to use in the heavy duty tractors, etc.

Bucky Harris

First Trip North

By Paul Kelley

Class B5A at Streator had finished on 14 Jan 61. Of the 8 of us in the class 3 had received assignments to FOX Sector. John Paul Gauthier, George Guerin and myself. John Paul stayed on at Streator for TTY (teletype) training while George, I and the others went down to Lackland AFB in Texas for two weeks of crypto training. We finished that on 31 Jan and had a few days off to get sorted before heading N. On 3 Feb I flew up to Montreal from New York and George came in from Boston, arriving about an hour before me, late in the afternoon. John Paul had already left a week earlier I think.

We met up at the Nordair hangar at Dorval. At this time Nordair still had the vertical contract, servicing Fox and Dye sectors. We were issued with our sleeping rugs, artic gear etc and advised that the flight north would be departing at about 2400.

As we had time to kill we stacked all our gear in a corner and decided to take a taxi to downtown Montreal for a few hours to do essential things like buy a good camera, set up an account with a tobacconist and treat ourselves to a slap up dinner – the last supper as it were.

About 2100 we headed back to the Nordair hangar at Dorval. If there was one thing we wanted to avoid at all costs it was missing the plane. The resulting embarrassment didn’t bear thinking about not to mention having to sit about for a week, at one’s own expense, waiting for the next flight. Needless to say we were back at the hangar with plenty of time to spare.

We then amused ourselves for the remainder of the time changing out of suits and ties (although some didn’t bother) into work clothes and packing all the fancy bits in clothing bags and suitcases. Then we made very sure that all of our artic outerwear – parka, trousers, mukluks, gloves etc – were of a good fit and in good condition. It turned out that mine was and the whole set was virtually new. Prior to boarding the aircraft we donned our new wardrobe.

We boarded our DC4 – CF-IQM (affectionately referred to in the local air-to-ground phonetic patois as Item Queen Mike) shortly before 2400.

We took off shortly after 0000 hrs and headed NNW. Our destination was Frobisher Bay 1288 miles distant. The adventure had begun and I was really up for it and soaking up every detail. There were about 15 passengers on board. Some were headed for Frobisher or onward to Cape Dyer but most to Hall Beach. George and I were the only radicians. The others were mechanics, riggers, logistical guys etc. We were seated in the aft end of the aircraft and the forward end was cargo and luggage tied down with netting. There were also two stewardesses on board which made for a bit of contrast with the stripped down interior, cargo etc. They served the meals en route which were very good considering that everything else was basic.

As soon as we were airborne from Dorval we headed N and the thing that struck me most was that, about 10 minutes later there was not a light to be seen. We were well into the wilderness already and I could but think of Ernest K. Gann’s Island in the Sky as I tried to visualise what it was like beneath us in the dark.

We were flying at an altitude of 5-6000 ft. Our first checkpoint would be Roberval, 219 miles N of Montreal. There we would join what was then designated Amber Route 10, an uncontrolled airway, and continue N 327 miles to Nitchequon. From Nitchequon we would continue 349 miles to Fort Chimo on the northernmost bit of Quebec on the S shore of the Hudson Straits. The last leg was 393 miles N to Frobisher Bay, the major town on Baffin Island and our first destination.

Shortly after takeoff, when we had settled down to our cruising altitude of circa 6k ft, the stewardesses served a meal and then we went to sleep. It was going to be the best part of a 7 hr flight to Frobisher so we might as well make the best of it. The drone of the engines soon put me out for the count. The cabin was heated after a fashion but the mukluks, trousers and parka made everything quite comfortable.

On the last leg of the flight we were served a breakfast and we arrived in Frobisher about 0700. Given the time of year it was still dark and would remain so for most of the day bar several hours between 1000-1400 when a form of daylight managed to emerge. We were going to be on the ground for 1-2 hours while they refueled, swapped cargo etc. Thankful now for our arctic gear, we all trooped through the gloom into the terminal building cum cafeteria. The temperature was about -10F but the wind was brisk – a first taste of things to come.

We hung around the terminal for a bit but, as a semblance of daylight began to appear, decided to take a short walk outside to see what we could see of our first sub-arctic settlement. Given the wind and blowing snow we couldn’t see much but were left with the impression that even if we could there wouldn’t have been much to write home about. It all looked pretty bleak with snow drifted over most buildings and the only really visible things being the telephone/power poles connecting these bulges in the snow.

As the daylight gradually began to win the struggle with darkness, the wind died down and the day improved markedly. When it was announced that everything was ready, more or less on schedule, we all trooped back to the aircraft, the interior of which was now circa -10F having had the cargo hatch open, for the final leg of our trip – 492 miles NW to Hall Beach.

We took off and George and I were enjoying our first aerial views of the arctic in the ‘daylight’ and getting some idea of the extent of Frobisher, albeit most everything was snow covered. After a few minutes, as we climbed over the wilderness of W Baffin Island, there wasn’t much to look at any more so we settled back and relaxed. I was in the window seat on the right side of the aircraft and George on the aisle. I just happened to glance outside and whoa! What do we have here?! Number 4 engine was on fire! I nudged George in the ribs and said ‘Guess what – number 4 engine is on fire. He mumbled something along the lines of pull the other one. No, seriously, look. He leaned over to look and was just a bit more voluble in his comments thereafter. I recall ‘This only happens in the movies’ as one of the more polite ones. None of the other passengers had apparently noticed this little phenomena yet. The aircrew obviously had as we began turning to the left almost as George ‘quietly’ brought what we noticed to the stewardess’ attention. Without missing a beat, she responded with ‘Cheer up, this is one of our better ones!’ – a remark I was unlikely ever to forget and definitely calculated to put everyone at their ease! By the time I looked out again the fire was out and we were dumping fuel en route back to Frobisher to land. Definitely an interesting start to our arctic adventure.

We landed uneventfully and all trooped back to the terminal building where we waited for about 2 hours while the mechanics got things sorted. Working on the tarmac at -10F in a hefty wind did not look like much fun. There were hangar facilities but whatever was wrong – and I never did find out what it was – was apparently correctable without too much fuss and bother.

During our second little sojourn we were getting a bit peckish so decided to have a snack of some sort. There wasn’t much on offer. I had a sandwich and a coffee – $C1 each!!! For $C1 down south you could buy a full breakfast. This introduction to the local economy came as a bit of shock. It was just as well we were being paid on an ‘all found’ basis or even our princely wage wouldn’t have lasted long at these rates.

We took off again in due course and this time it was all boringly uneventful, just as it should be. The 492 mile flight NW to Hall Beach was going to take just under 3 hrs. The gals served another meal and then we sat back and relaxed as we passed over the Arctic Circle (66-30N) for the first time and droned on over the featureless ice of Foxe Basin.