IceCap-1 (DYE-2)

July 14-19, 2003.

Editor’s note: Gazette Reporter Michael Lamendola spent the week of July 14-19 with the 109th Airlift Wing in Greenland, at their invitation. He traveled with the unit on training trips and excursions into the countryside. Part of those travels took him to the now-abandoned DYE-2 site.

By MICHAEL LAMENDOLA Gazette Reporter

CAMP RAVEN, Greenland

From the cockpit of the LC-130 Hercules, the Greenland Ice Sheet stretches endlessly toward the crystal-blue horizon. It is flat, stark white and devoid of any natural landmarks. Yet, somewhere in this vast emptiness is the plane’s destination, an isolated place called Camp Raven. A speck of a life on an immense floating sea of ice, Camp Raven is the 109th Airlift Wing’s training site for airborne radar approaches. The Air National Guard unit is based in Glenville. For more than a decade, 109th air crews have come to Greenland to hone their piloting and navigating skills over the ice and to support National Science Foundation scientific research missions there.

“They fly as many training missions as permitted and fulfill the airlift needs of the science community. This is the only place they can train to get qualified,” said Maj. Jody Ankabrandt, 109th public affairs officers. For five months out of the year, in almost daily flights, 109th navigators and pilots learn how to approach the tiny camp using only the Hercules’ on-board radar and their eyes. “Civilian airports have instruments that communicate with pilots on approach. We can’t use global position system approaches yet, so all we have left is radar,” said Maj. George Alston, 109th supervisor of flying.

On this training mission, the plane has two “rookie” navigators and a co-pilot. Although the men have years of experience and are qualified to fly the LC-130, they are rookies in that they’ve never flown or navigated the plane over ice using only onboard radar. Once their training is complete, then and only then can they participate in the 109th’s main mission: To fly support for the National Science Foundation research stations in Antarctica later in the year. The 109th assumed this mission in 1999. It is the only military unit in the world that flies ski-equipped LC-130s. The cargo planes can carry 45,000 pounds for 356 miles at 350 mph. The science foundation’s Antarctica program is budgeted at nearly $ 250 million annually.

Flight to Raven

The flight to Raven takes about 30 minutes from Kangerlussuaq (Kangger loose work), the 109th’s base of operations on the western coast of Greenland. Several miles out from Raven, a seasoned navigator begins to call out numbers _ altitude, heading, distance. He reads from a banks of instruments before him and from a little glowing green screen that shows an electronic image of the area. The co-pilot takes careful note of the numbers, adjusting the plane on the heading given by the navigator. They are his only reference sources, as there are no beacons or no ground-based radar to serve as guides over the trackless ice. There is only the navigator.

“The navigator will verbally paint a picture for the co-pilot, so that the pilot will be able to look up and see what the navigator has described,” Alston said. Minimum landing conditions require that the pilot see the skiway one mile out from an altitude of 300 feet. Air crews rely on close-proximity identification and the plane’s instruments for other reasons. The featureless ice affects depth perception, causes vertigo and creates optical illusions.

“Everything is white. There are no points of reference,” said Master Sgt. Ron Trippodo, who has deployed to Greenland with the 109th since 1985. While the LC-130 can do a “zero/zero landing” zero visibility with zero ceiling it’s a rare occurrence, Alston said.

Landing at Raven

Visability is unlimited on this mission, and the plane lands at Raven without a hitch. As soon as it hits the skiway, the pilot reverses the plane’s engines; this is the only way to stop on the ice. While the plane remains on the ground, its four turboprop engines continue to roar; shutting them down is too risky. At Raven, Tracy Dahl greets passengers and collects the unloaded supplies. Dahl, 44, and his wife, Amy, 38, live at Raven during the 109th’s training season. They are civilian contractors who maintain the skiways, gauge weather and, on occasion, play host to visitors. Grizzled and sunburnt, the Dahls love the isolation of their workplace and the freedom it provides. “I want to be able to control how much civilization I’m exposed to,” Tracy Dahl said. Civilization is indeed at a premium at Camp Raven. The camp consists of two ski-ways, a large tent, an unheated outhouse and several storage buildings. Wildlife is scarce and the nearest neighbor is more than 100 miles away.

Married for more than five years, the Dahls are spending their second season at Raven. They spend a lot of time together. They have wintered together for months on the Antarctica Ice Shelf and, when not working, reside on a secluded mountain in Colorado, where they’re creating a self-sufficient homestead. Close communications has helped them survive their constant intimacy, Tracy Dahl said. “We have to be able to work out our problems immediately,” he said.

They have no children and don’t plan to have any: “Children wouldn’t be able to adapt to our lifestyle,” Tracy Dahl said. “Besides, if we want children there are plenty to adopt.” Amy Dahl said her family has mixed reactions to her lifestyle. “My mother thinks its unusual. She wants me to have a regular job. I have a regular job; it’s just in a different country. And some of my family think what I do is neat,” she said. Their home is a one-room tent the size of a large car garage. It contains all the necessitates they require to survive: heat, water, food, power and entertainment, consisting mostly of books and music. Power comes from a solar windmill and batteries; the Dahls are eco-conscious. During a recent visit, Amy was baking bread. The inside of the tent was a snug 80 degrees; the outside temperature measured 30 degrees.

On some days, conditions are so mild the Dahls can work in shirts. But just as easily, they can find themselves trapped inside their tent for days at a time. The day before, for instance, winds measuring 50 mph pounded Raven. Despite their isolation, the Dahls have received dozens of visitors this year. Visitors know about Raven and often stop by to escape fickle weather or to check in. On those occasions, they can sign the Dahl’s guest book, which sits next to a plate of homemade cookies and boxes of different teas.

Visiting Dye-2

One of Tracy’s unofficial duties this visit was to take visitors to Dye-2, a relic of the Cold War about one mile distance from the camp. Dye-2 is one of 58 Distance Early Warning Line radar stations built by America between 1955-1957 across Alaska, Canada, Greenland and Iceland at a cost of billions of dollars. Their powerful radars monitored the skies constantly in case Russia decided to send bombers towards America.

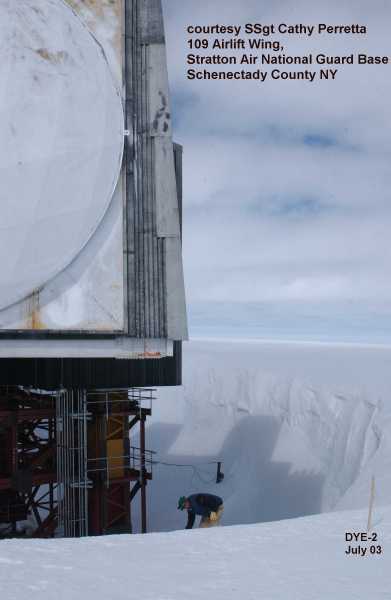

The DEWLine was closed between 1963 and 1995 as modern technology made them obsolete. Dye-2 was hastily abandoned in 1988. A massive structure, Dye-2 measures 200 feet along the sides and reaches six stories to the radar dome. The building sits on six huge steel-girder pylons that rise 30 feet above the snow. The pylons are buried in the ice, and the station could be raised or lowered on them to compensate for shift. From a distance the structure, with its onion-shaped dome, looks like a Russian orthodox church.

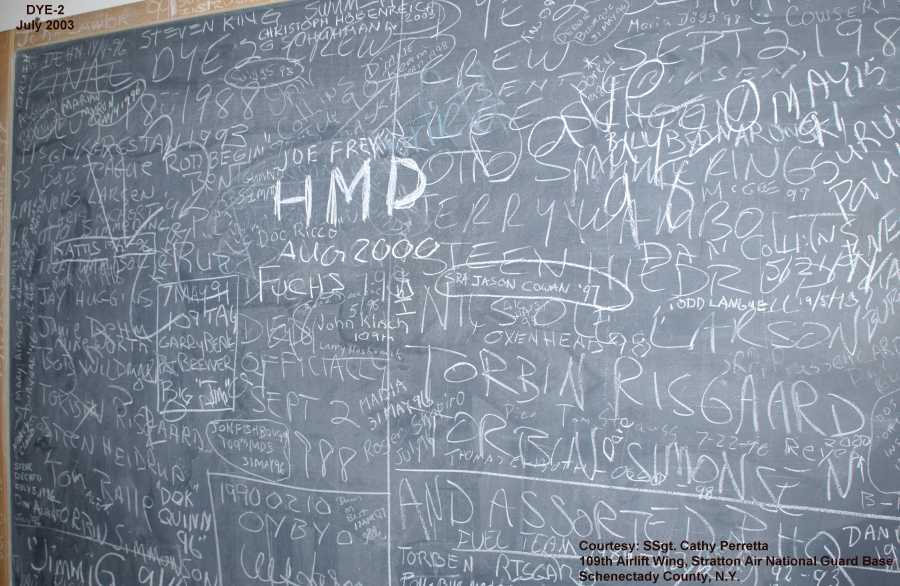

The interior shows signs of a quick exit. Dated magazines and calendars are strewn about. Freezers still contain food and technical equipment worth tens of thousands of dollars is every where. The site has the nickname “Dye-mart” among the locals who have “shopped” there for nuts and bolts, toilet paper and other items. The building has been vandalized over the years. Garbage and mattresses fill the kitchen area. Doors once sealed against the cold have been left open, and snow drifts now fill some rooms.

Terry Wambolt worked as a console operator at Dye-2 in the 1980s and remembers the site’s last days. “I woke up one morning to a lot of noise in the hallway. I walked out of my room to see everyone packing their belongings,” said Wambolt, who now works in Venezuela. The staff, Americans and Danes under private contract with the Air Force, were told the building was in danger of collapsing and had to leave immediately. They took only their personal belongs and kept the station going until the last second. Wambolt said he was talking with a Canadian military official “when we pulled the plug on the link.”

He returned two weeks later with a crew that dismantled the equipment and was literally the last person to leave Dye-2. “We were very busy during this time and I was sad to see it end. I remember thinking of all the waste,” he said. The site is slowly disappearing into the snow. Its outbuildings are no longer visible and drifting snow will consume it completely one day, but that day appears to be decades away.

Planning a mission

Although the months of June through September are considered summer in Greenland, the weather on the ice is unpredictable, especially at the remote scientific research camps the 109th supports.

“Weather conditions are the No. 1 factor that affects a mission, followed by crew conditions and the customer’s needs,” Alston said. The 109th has a contract to supply support services to the science stations on the ice sheet. “Everything is driven by crew rest. Safety is always a primary concern. After that, we look at maximizing training and the priorities of the customer,” Alston said.

Putting a mission together “is like a giant jigsaw puzzle. And this is a jigsaw puzzle that you can put together in four or five different ways,” Alston said. When all the factors come into play, “plans can change within seconds,” requiring the 109th and its customers to exercise maximum flexibility, he said. Weather conditions at mid-week forced the 109th to reschedule several flights to Camp Summit and North GRIP, causing a ripple effect on the 109th’s other missions. Summit is a National Science Foundation site studying air-snow interactions and global warming. It is located 248 miles from the nearest point of land, at the peak of the ice cap. One of the current experiments there involves the testing of a device called “Tumbleweed” for NASA. Tumbleweed is a canvas-covered ball containing sensors. It is designed to move along the surface using the winds. If testing at Summit is successful, the device could find itself on Mars some day.

GRIP

The Greenland Icecore Programme is a European research program conducting ice-core sampling. It is located 492 miles northeast of Kangerlussuaq. Here, scientists during the week succeeded in sinking a drill to Greenland’s bedrock through nearly two miles of ice. The ice core samples they removed span nearly 250,000 years of history. The information they contain will allow scientists to study climatic and atmospheric changes through time.

The area

The Greenland Ice Sheet is approximately 3 million years old and is more than 2 miles thick. It covers more than 95 percent of the island and is the second-largest glacier in the world. It is constantly moving toward the sea, where it “calves” icebergs. Portions of the ice sheet can be reached by vehicle from Kangerlussuaq, a hamlet of approximately 300 people. Kangerlussuaq, which means long fjord in Greenlandic, is a company town that supports operations of the international airport there. One her first trip to Greenland, Lt. Michelle Dix, the 109th’s medical officer on the trip, found the place “intriguing. Everyone goes by and waves.” Another first timer, Master Sgt. Hank Fountain, said he was glad he came.

“It’s great. I wasn’t sure what to expect, but this is totally different from base work,” he said. He summed up the feelings of many members of the 109th who come to Greenland each year: “Everything is about the mission, and we’re doing something to help. It’s great to be involved.”

Following photos of the DYE-2 complex were taken during the visit by SSgt Cathy Perretta, 109 airlift Wing, Stratton Air National Guard Base, Schenectady County, NY.

Picture Gallery

(Clicking on a picture will open a full size image in a new window.)